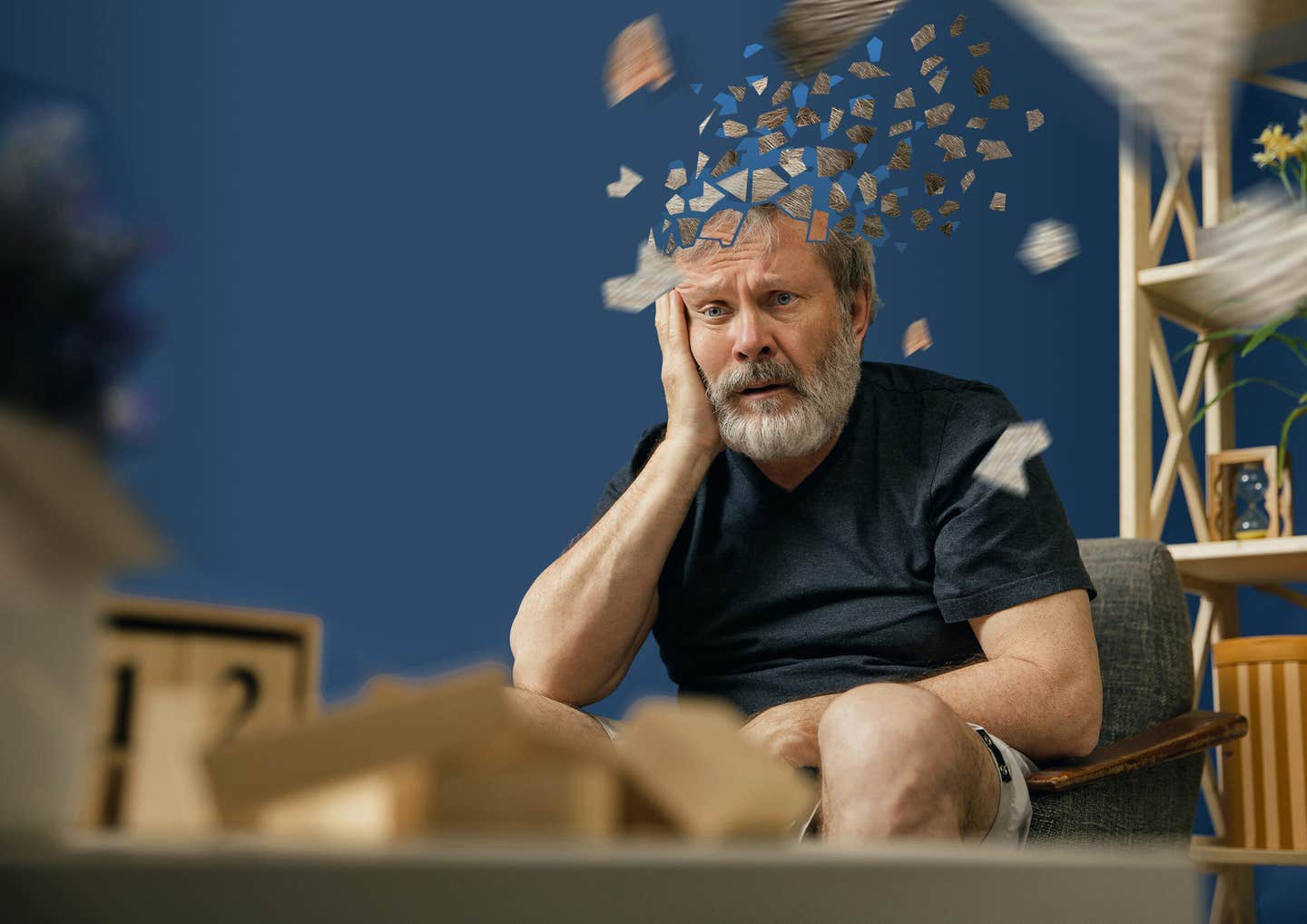

‘Fart gas’ linked to memory loss and Alzheimer’s-like brain damage, study finds

An NIH-funded Johns Hopkins study finds that removing one enzyme, CSE, can trigger progressive memory loss and Alzheimer’s-like brain changes in mice.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Johns Hopkins researchers tie loss of the CSE enzyme to memory decline and Alzheimer’s-like brain damage in mice. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

Researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine, led by Bindu Paul, an associate professor of pharmacology, psychiatry and neuroscience at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, reported new evidence that a single brain enzyme may be central to memory.

The National Institutes of Health-funded study, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, focused on cystathionine γ-lyase, or CSE. CSE helps generate tiny amounts of hydrogen sulfide in neurons, a gas better known for the smell of rotten eggs.

The project also drew on decades of work from Solomon Snyder, professor emeritus of neuroscience, pharmacology, and psychiatry at Johns Hopkins Medicine and a co-corresponding author. Snyder’s laboratory previously linked CSE to brain protection in Huntington’s disease models. Later work suggested CSE function falters in Alzheimer’s models. This new study asked a cleaner question. What happens when CSE alone disappears?

“This most recent work indicates that CSE alone is a major player in cognitive function and could provide a new avenue for treatment pathways in Alzheimer's disease,” says co-corresponding author Snyder, who retired from the Johns Hopkins Medicine faculty in 2023.

Why a “rotten egg” gas matters in the brain

The brain relies on tiny chemical messengers that help cells communicate and handle stress. Hydrogen sulfide, often shortened to H2S, is one of them. Three enzymes can produce it in the brain, including CSE, CBS, and 3-MST. Scientists long treated CBS and 3-MST as the main brain sources. CSE often got more attention outside the brain.

Paul’s group argued that view may miss something important. CSE is mostly found in neurons. It can shape H2S signaling in ways that affect proteins, stress control, and cell survival. Prior studies also suggested a tricky balance. Too little H2S may harm brain function. Too much can also cause damage.

That balance creates a practical problem for drug development. Paul said earlier work points to hydrogen sulfide as protective in mice. Yet H2S becomes toxic at higher doses, which rules out simply delivering it to the brain. The safer path may be learning how to maintain normal signaling at extremely low levels, and finding ways to support the system without overdosing it.

A clear behavioral signal in aging mice

To isolate CSE’s role, the team studied genetically engineered mice that lack the CSE enzyme. They compared those mice with normal mice using a spatial learning task called the Barnes maze. In that test, mice learn to find an escape hole on a platform when a bright light shines.

At two months, both groups performed similarly. At six months, the difference was stark. The CSE-lacking mice struggled to find the escape route, while normal mice still learned the task.

“The decline in spatial memory indicates a progressive onset of neurodegenerative disease that we can attribute to CSE loss,” says first author Suwarna Chakraborty, a researcher in Paul's lab.

The researchers checked for simpler explanations. The memory deficit did not match a movement problem. The mice showed comparable locomotion and body weight. Their smell and basic sensorimotor function also looked similar. That pattern suggested a cognitive change, not a general health decline.

Damage signs appear across the hippocampus

The team then examined the hippocampus, a brain region tied to learning and memory. They found multiple warning signs that echo Alzheimer’s biology. Paul said the CSE-lacking mice showed more oxidative stress, more DNA damage, and weaker blood-brain barrier integrity.

Co-first author Sunil Jamuna Tripathi summarized the scope of the impairment. “The mice lacking CSE were compromised at multiple levels, which correlated with symptoms that we see in Alzheimer’s disease,” says co-first author Sunil Jamuna Tripathi, a researcher in Paul's lab.

The study included broad protein surveys of hippocampal tissue. Many proteins linked to synapses and transport shifted in the CSE-lacking mice. Markers tied to oxidative stress rose. Proteins connected to iron handling also changed, which mattered because excess iron can become toxic in brain tissue.

Direct tests backed up those signals. The researchers measured higher levels of lipid damage markers in hippocampal subregions. They also found stronger evidence of DNA lesions, including markers linked to oxidized DNA bases and double-strand breaks.

A leaky barrier and fewer newborn neurons

"The blood-brain barrier normally limits what enters brain tissue from the bloodstream. Using high powered electron microscopes, our team saw breaks consistent with barrier disruption. They also found evidence that immune proteins, such as IgG, crossed into brain regions where they should be limited," Tripathi told The Brighter Side of News.

"Our research team also tracked neurogenesis, the production of new neurons in the hippocampus. That process tends to decline with age and neurodegenerative disease," he continued.

In the CSE-lacking mice, markers of immature neurons dropped sharply at older ages. Stem cell division markers also fell, and fewer newborn neurons survived over time.

The team connected these changes to a pathway often tied to memory. They reported weaker activation of CREB, a protein that helps switch on genes needed for learning. They also reported changes in BDNF, a well-known molecule linked to synaptic plasticity.

Practical Implications of the Research

More than 6 million people in the United States have Alzheimer’s disease, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and prevalence is on the rise. The study does not offer a cure. It does sharpen a potential target that sits upstream of several problems seen in Alzheimer’s disease biology, including oxidative damage, iron imbalance, blood-brain barrier weakness, and reduced neurogenesis.

If future work confirms the same biology in people, CSE could guide new strategies that aim to preserve brain resilience rather than chase one symptom. That could mean drugs that boost CSE activity or stabilize its signaling, while avoiding unsafe H2S exposure.

The findings could also help researchers track earlier disease stages. Several of the measured changes, including barrier integrity and iron handling, may offer clues for biomarker development. Over time, that mix could support earlier detection and better-designed therapies that slow decline.

Research findings are available online in the journal PNAS.

Related Stories

- Researchers transform ‘sewer gas’ into clean hydrogen fuel

- Fart gas may hold the key to a longer, healthier life

- The surprising science behind flatulence and gut health

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.