First-confirmed images of microplastics in the brain — possible link to dementia

First confirmed images of microplastics in human brains raise questions about dementia and long term health effects.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

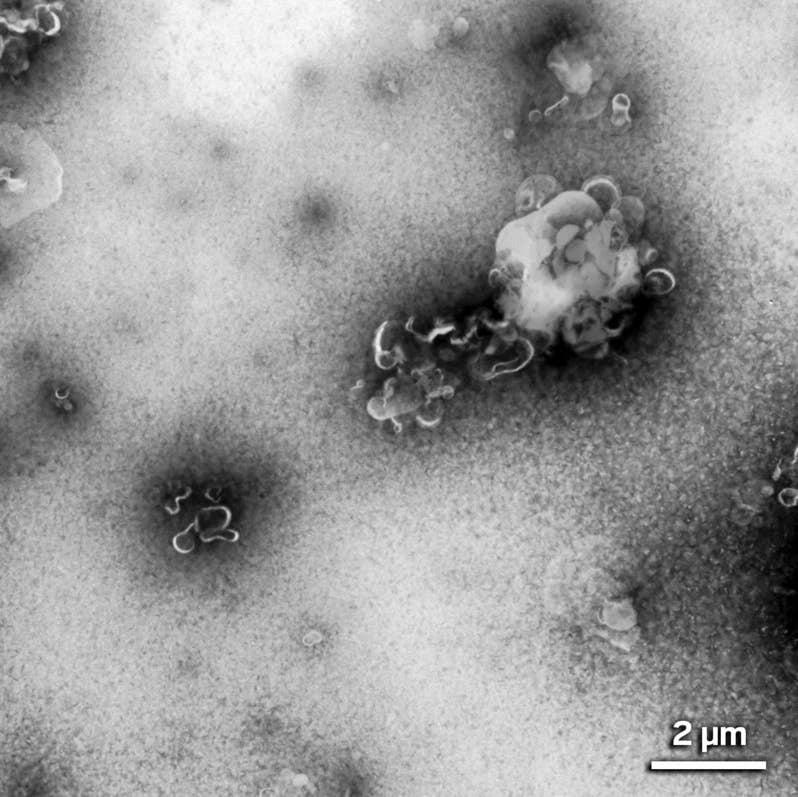

Elaine Bearer found that the microplastic clumps taken from brain samples are actually clusters of hook-shaped nanoplastics. (CREDIT: Elaine Bearer)

Strange brown specks in two donated brains set a seasoned neuropathologist on an unexpected path. Elaine Bearer had examined countless samples during her long career, yet these glassy clusters puzzled her. They refused to take up any stain. They offered no clues under standard imaging. And they appeared in the brains of people who had lived with dementia, which made their presence even harder to ignore.

Bioaccumulation of Microplastics

A few months passed before a chance conversation pointed her in a new direction. A colleague at the University of New Mexico, Matthew Campen, had been testing human brain tissue for microplastics using a technique called pyrolysis gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. His findings were published in the journal Nature Medicine.

His team examined tissue from people who died in 2016 and 2024 and discovered that the brain held far more microplastics than the liver or kidneys. The levels also rose sharply over time, suggesting that everyday exposure to plastics is leaving a growing mark inside the body. “Compared to autopsy brain samples from 2016, that’s about 50% higher,” he said. “That would mean that our brains today are 99.5% brain and the rest is plastic.”

When Bearer heard about his work, she sent over a small piece of tissue from the mysterious deposits. The findings were hard to overlook. The dementia-affected samples held five times more microplastics than the comparison tissue taken from people without dementia.

Even with that information, she still felt unsure. The chemical signals suggested plastic, but she had no way to match those results to the brown lumps she saw under the microscope. Pathologists in other labs had noticed similar deposits, yet no one had linked them to a specific material. The uncertainty pushed her forward.

New Tools for a New Problem

Bearer turned to electron microscopy to study the particles Campen’s team had isolated. These tiny fragments were far smaller than cells and even smaller than many viruses. Some were close to the size of DNA strands. Under high magnification, she noticed small hooked shapes with sharp points. She realized that the plastic in human brains was not only present, but surprisingly small. The fragments were so tiny that common diagnostic tools could not detect them. Pathologists had likely been overlooking them for years.

Finding the particles inside intact tissue proved far more difficult. Bearer tried more than a dozen stains, several antibodies, and multiple imaging systems. Each attempt produced the same result, a blank field of view. Conventional electron microscopy also failed because the method embeds tissue in plastic. That meant the sample plastic blended with the very particles she hoped to study, leaving no contrast.

During a month-long visit to the California Institute of Technology, frustration built as technique after technique fell short. Then she visited a colleague who managed a laser scanning confocal microscope. Together they cycled through ten lasers and eight detectors. One combination finally worked. The particles absorbed light at one wavelength and released it at another. When that glow appeared across the screen, Bearer felt certain she was looking at microplastics inside human brain tissue for the first time.

Her team later posted their method on bioRxiv in late 2024. It marked the first confirmed sighting of microplastics within human brain samples using microscopy.

What the Deposits Might Mean

The two original samples showed a strong link between plastic particles and dementia. As Bearer expanded her work to ten more donated brains, she found plastic in every single one. None were free of synthetic fragments. She now wants to understand where the particles collect, how deeply they settle, and whether they affect the cells around them. She stresses that no proof yet ties these particles to disease. They may contribute to harm, or they may do nothing. The only clear fact is their presence.

Bearer hopes to go further by using magnetic resonance imaging to track the particles in living people. Her plan is to pair MRI with magnetic resonance spectroscopy, a method that identifies the chemical makeup inside tiny regions of tissue. She admits this goal sits on the horizon, but she believes it could help scientists measure a person’s plastic load while they are alive. That kind of real-time monitoring may one day guide efforts to reduce plastic exposure.

A Wider Environmental Story

Microplastics already appear in the ocean, soil, food, and water. They move through the bloodstream and settle in organs throughout the body. Their effects remain under study, but many scientists worry that they may disturb cell function and trigger inflammation. Reactions like these can shape long-term health. Conservation groups warn that wildlife faces similar risks, which could chip away at biodiversity.

The steady spread of plastics has been driven by daily habits. Everyday containers, disposable packaging, synthetic clothing, and cosmetic products all shed small plastic dust into the environment. Health groups encourage people to lower this exposure by using glass or metal for heating food, filtering tap water, choosing clothing made from natural fibers, and reducing the use of disposable plastics.

For now, the study offers a stark reminder that the plastic filling our environment isn’t staying outside. It’s crossing into some of our most sensitive organs, and researchers say understanding how and why is becoming urgent.

Related Stories

- Revolutionary new plastic fully dissolves in seawater leaving no microplastic waste

- Teabags release billions of microplastic particles into a single cup

- Scientists Discover a Simple Trick to Eliminate Microplastics From Tap Water

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Writer

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs to historical discoveries and innovations. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.