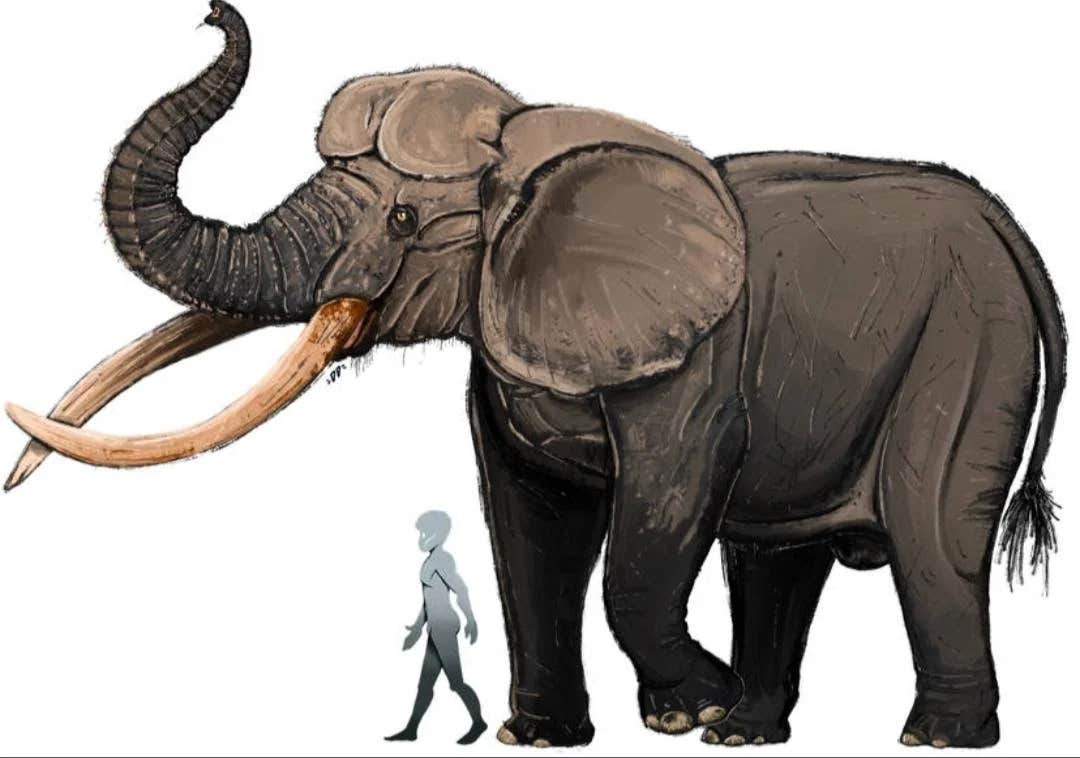

Giant elephant skull fossil offers a rare glimpse into the ancient giant’s past

Alongside the skull, researchers uncovered 87 stone tools hinting at a deep and complex interaction between early humans and these elephants.

A prehistoric elephant skull unearthed in Kashmir is shedding new light on Middle Pleistocene evolution and humanity’s ancient ties to megafauna. (CREDIT: astrapionte)

A fossilized elephant skull found in the Kashmir Valley is reshaping how scientists understand an ancient giant’s past. Discovered in 2000 from the Karewa sediments near Pampore, the skull remained a quiet mystery until its recent publication in Vertebrate Paleontology. It belongs to the genus Palaeoloxodon, a group of straight-tusked elephants that once thundered across Africa, Europe, and Asia.

What makes this find so valuable isn’t just its age or size—it’s the context. Alongside the skull, researchers uncovered 87 stone tools. These artifacts hint at a deep and possibly complex interaction between early humans and these elephants. The Karewas, with their layered lake and riverbed deposits, have long been a rich record of life in the region. But this skull, preserved with remarkable detail, stands out.

The fossil quickly drew attention from scientists worldwide. Researchers from the Florida Museum of Natural History, the British Museum, and the Natural History Museum in London teamed up to study it. Their collaboration marks one of the most detailed investigations into an Indian Palaeoloxodon specimen.

The skull itself tells a curious story. It has a wide, flat forehead, much like the more advanced Eurasian species. But something’s missing: the pronounced parieto-occipital crest. This bony ridge, found atop the skull, usually grows with age in male elephants and signals sexual maturity. Its absence here raised questions.

Dr. Steven Zhang, a palaeontologist at the University of Helsinki, was part of the team. “From the size, the wisdom teeth, and other features of the skull,” he said, “it is evident this was a majestic bull elephant in the prime of its life. Yet, the underdeveloped crest suggests a distinct species.”

That subtle difference has turned into a major clue. The skull’s features don’t quite match those of the better-known European Palaeoloxodon antiquus. Instead, they more closely resemble those of Palaeoloxodon turkmenicus, an elusive species described from a lone skull found in Turkmenistan during the 1950s.

Related Stories

For years, the Turkmen specimen sparked debate. Was it a one-off variation of the European species, or something entirely separate? Without more fossils, researchers couldn’t say for sure. But this new skull from Kashmir now gives weight to the idea that P. turkmenicus was its own species, not just an odd outlier.

Its discovery suggests that this rare elephant may have roamed a wide area—from Central Asia deep into northern India. The Kashmir skull doesn’t just fill a gap in the fossil record. It opens a new chapter in the story of these long-lost giants and their journey across continents.

The Karewas, where the fossil was discovered, are sedimentary formations nestled within the intermontane basin of the Kashmir Valley. These layers date back to the Plio-Pleistocene, offering a window into ecosystems that thrived millions of years ago.

The Pampore Member, which yielded the skull, consists of laminated sands, clays, and silts. This formation is part of the upper Karewa Group, known for its rich fossil deposits.

Fossil evidence suggests that Palaeoloxodon originated in Africa around one million years ago before dispersing into Eurasia. Early African forms exhibited a narrow, convex forehead and minimal crest development. Over time, more derived species in Europe and Asia developed wide, flat foreheads and prominent skull crests.

The Kashmir skull’s intermediate features provide crucial data for understanding the evolutionary trajectory of these massive elephants.

Dr. Advait Jukar, a lead researcher at the Florida Museum of Natural History, explained, “With its wide, flat forehead and faint trace of a crest, P. turkmenicus may represent a missing link in the evolutionary history of Palaeoloxodon. This species bridges the gap between primitive African ancestors and the more advanced Eurasian forms.”

The 87 stone tools discovered alongside the Kashmir skull hint at interactions between early humans and these prehistoric giants. These tools, likely used for butchering or other purposes, provide indirect evidence of human activity in the region during the Middle Pleistocene. This period, dating back 300,000 to 400,000 years ago, aligns with the estimated age of the skull based on protein decomposition in its tooth enamel.

The association of the tools with the fossil emphasizes the ecological and cultural significance of Palaeoloxodon. These elephants likely played a vital role in the lives of early humans, serving as sources of food, tools, and even inspiration for early art and storytelling. The co-occurrence of these artifacts and remains underscores the interconnectedness of species in prehistoric ecosystems.

Despite their size and prominence in ancient landscapes, much about Palaeoloxodon remains unknown. Fossil evidence from the Karewas and surrounding regions has been sparse compared to the more extensively studied Siwalik Hills to the south. The Kashmir skull, along with the Turkmen specimen, provides rare insights into the diversity and distribution of these extinct megaherbivores.

Researchers suggest that P. turkmenicus represents a transitional species. Its features bridge primitive African Palaeoloxodon recki and advanced Eurasian forms like P. antiquus. By combining morphological studies with advanced techniques such as protein decomposition analysis, scientists are piecing together the puzzle of this genus’s evolution.

Dr. Zhang highlighted the broader implications of the findings, stating, “These discoveries not only enrich our understanding of Palaeoloxodon but also illuminate the ecological and evolutionary pressures that shaped life in the Pleistocene.”

The Kashmir Palaeoloxodon skull stands as a testament to the intricate web of life that once flourished in the intermontane valleys of the Himalayas. Its discovery has reignited interest in the region’s fossil record, inspiring new studies on the Karewa sediments and their rich history.

As scientists continue to explore the evolutionary journey of these prehistoric giants, the Kashmir skull reminds us of the delicate balance of ecosystems past and present. This fossil is more than just a relic; it is a bridge connecting us to a time when Earth’s landscapes were dominated by creatures of extraordinary size and complexity.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.