Humpback whales are making a major comeback – here’s why

Not long ago, spotting a humpback whale in Arctic seas felt like winning a lottery ticket. In the early 2000s, University of Southern Denmark whale researcher Olga Filatova spent years searching…

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Humpbacks once hovered near extinction. A new Arctic study reveals how switching food sources helped them rebound and thrive. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

Not long ago, spotting a humpback whale in Arctic seas felt like winning a lottery ticket. In the early 2000s, University of Southern Denmark whale researcher Olga Filatova spent years searching before seeing her first one. Today, she sees them almost daily during fieldwork in the far north. The change is striking, and it carries a message about survival, flexibility and hope.

“Back then, it was incredibly rare,” Filatova says. “Now we see them almost every day when we’re in the field. We don’t know the exact number, but there are many more than when I started.”

That rebound is no small thing. A cautious estimate from the Endangered Species Coalition places the global population near 80,000, far above the estimated 10,000 at their lowest point. Commercial whaling was banned in 1986, and that decision helped spark one of the most remarkable wildlife recoveries of the modern era. But protection alone does not explain how humpbacks thrive. Their real edge, it turns out, lies in how they eat.

Following the Food, Not the Crowd

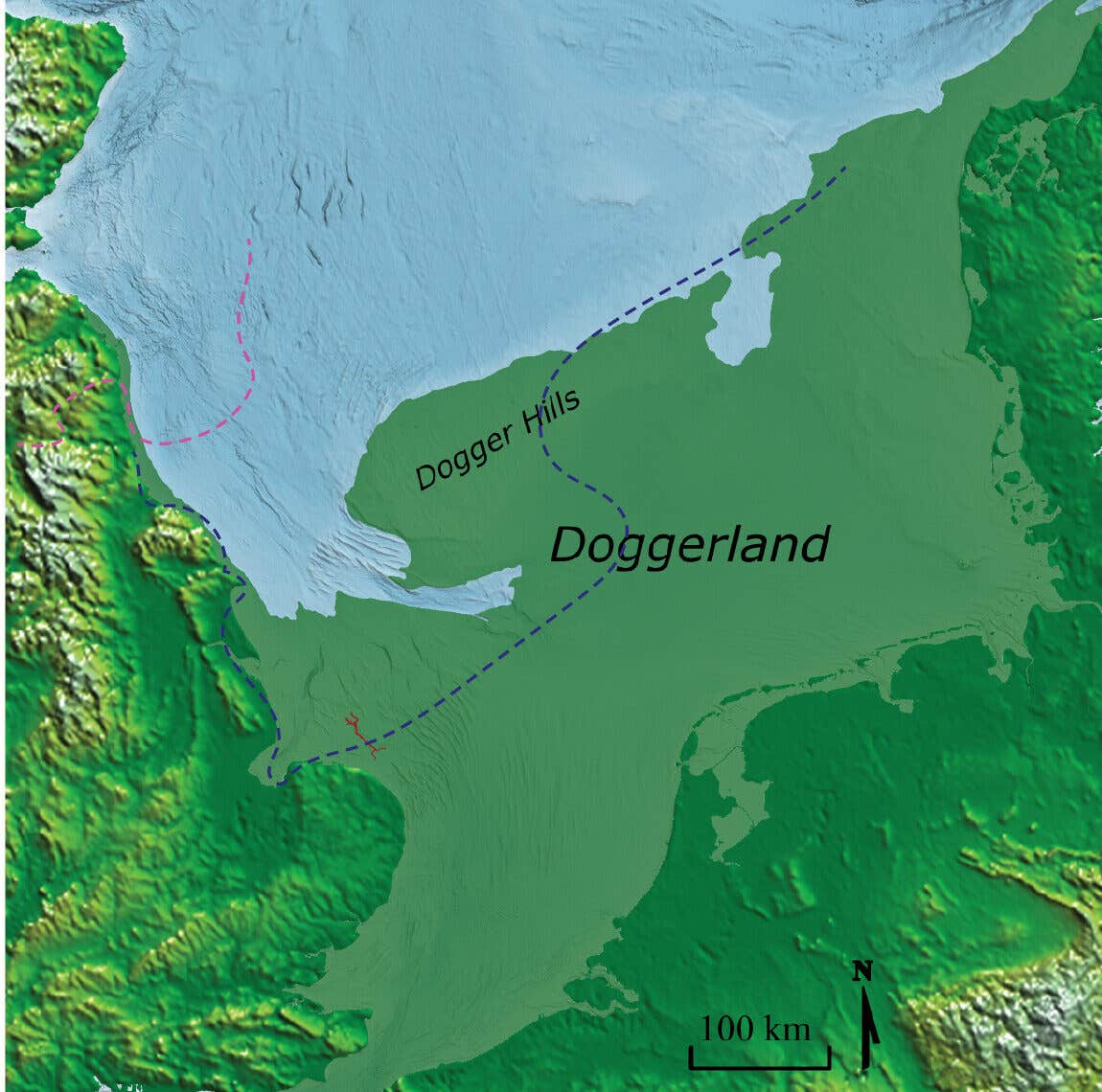

Between 2017 and 2021, Filatova and her team tracked humpbacks during summers and falls in Senyavin Strait, off Russia’s eastern Chukotka Peninsula. The waters border the Bering Sea and pulse with life. Over five years, researchers recorded where whales gathered, how they fed, and what they left behind in chemical clues carried in their skin.

In 2017, something unusual happened. Roughly 100 humpbacks packed into the strait to hunt polar cod, a fish that had formed a rare and sudden school. The next year, the cod vanished. The whales did not.

Instead, they pivoted.

From 2018 through 2021, the team watched the same population shift to a new main course. They began chasing swarms of krill, tiny crustaceans that form clouds in cold waters. The whales’ behavior changed, their feeding spots moved, and even the chemical signals in their bodies confirmed the switch. The study, published in the journal Marine Mammal Science, shows just how fast humpbacks can change their habits when conditions turn.

“Unlike several other whales, humpbacks will stay in one area even if a favorite food disappears, as long as something else is available,” Filatova says. “We saw them hunt cod one year and krill the next. That tells us a lot about why this species does so well.”

Reading a Whale’s Menu

Most feeding happens far below the surface, beyond easy view. To solve the mystery of what whales eat, scientists turned to stable isotope analysis. By sampling whale skin, they measured forms of nitrogen that change depending on what an animal consumes.

Higher nitrogen readings point to fish. Lower ones signal krill.

The method works because heavier forms of nitrogen build up as animals climb the food chain. In Senyavin Strait, the numbers told a clear story. The whales ate fish in 2017. In later years, krill took over.

This is not just about diet. It is a window into how oceans shift and how creatures respond. Humpbacks, with the most varied diet among rorquals, act like living gauges of marine change.

Low Speed, High Ingenuity

Humpbacks are not built for sprints. They are bulky, with long, awkward flippers. Yet they have a reputation as inventive hunters who conserve energy by outsmarting prey.

One trick is known as “trap feeding.” A whale floats at the surface with its mouth open while seabirds dive for fish. The fleeing fish dart straight into what they think is shelter and land in danger instead. It is slow, quiet and effective.

Other whales chase favorites across large distances. Humpbacks show another path. They stay put, sample what is around, and adapt.

“They’re not fast,” Filatova says. “But what they lack in speed, they make up for in creativity and willingness to eat what’s available.”

A Changing Arctic, A Moving Giant

Humpbacks also benefit from a warming world in ways other whales do not. As sea ice retreats, new stretches of water open for feeding and travel. Reports now place humpbacks in Arctic waters where they were once unknown.

The species migrates vast distances each year, moving from warm breeding grounds to polar feeding areas and back again. Some travel more than 15,000 miles annually. Their size is staggering. Adults reach up to 62 feet and can weigh 35 tons. Females, the largest, give birth every two to three years after nearly a year of pregnancy. Many live for decades.

Filatova remains calm about their future.

“I’m not worried about humpbacks,” she says. “I’m worried about whales that can only live in Arctic waters, like bowheads, belugas and narwhals.”

Those species face shrinking habitats with fewer escape routes.

A Signal Written in Water

What happened in Senyavin Strait offers a lesson beyond whales. It reveals how fast ecosystems can change and how survival depends on flexibility. A single population switched prey in a matter of months. That kind of readiness may explain why humpbacks survived where others struggled.

They are not just fewer animals now spared by law. They are active shapers of their fate.

Their return is a reminder that protection works, but nature also rewards those that adapt. In the end, a whale’s greatest strength may not be its size, but its refusal to be tied to one path.

Practical Implications of the Research

This research helps scientists track ocean health through whales that respond quickly to change. By studying their diet shifts, researchers can spot early signs of trouble or recovery in marine ecosystems. The findings also guide conservation by showing which habitats matter most and when.

For the public, the work underscores the value of environmental policies like whaling bans and climate action. Healthier oceans support not only whales, but fisheries, coastal communities and the global food system.

Understanding how adaptable animals survive may also help protect species that cannot move or change as easily.

Research findings are available online in the journal Marine Mammal Science.

Related Stories

- Bowhead whales may hold key to humans living for centuries

- Filmed for the first time: Killer whales attack and kill great white sharks

- Wild killer whales spotted sharing their food with humans in multiple acts of kindness

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Writer

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs to historical discoveries and innovations. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.