Most distant spiral galaxy ever found shatters theories of cosmic formation

Discovered just a billion years after the Big Bang, Zhúlóng is the most distant spiral galaxy ever found—and it changes everything.

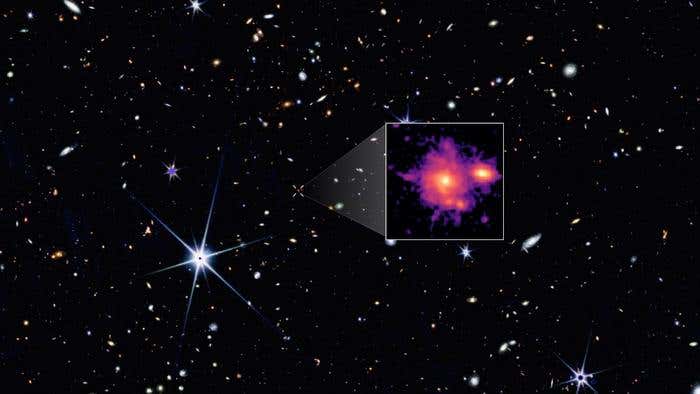

JWST spots the most distant spiral galaxy yet, shaking up what we know about early galaxy formation. (CREDIT: NASA/CSA/ESA, M. Xiao (University of Geneva), G. Brammer (Niels Bohr Institute), Dawn JWST Archive)

In the vast darkness of the early universe, a spiral of light named Zhúlóng offers a new glimpse into cosmic history. This galaxy, shaped like our Milky Way, formed just a billion years after the Big Bang. It wasn’t supposed to exist so soon. But thanks to the powerful James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scientists are now questioning what they thought they knew about how galaxies grow.

Galaxies were once thought to start out as messy blobs, slowly growing more organized over billions of years. Large, structured galaxies with spiral arms and central bulges, like the Milky Way, were expected to take time to evolve.

But JWST is telling a different story. With its deep infrared vision, it has revealed galaxies that are big, bright, and surprisingly mature – much earlier than anyone expected.

Among the most surprising of these is Zhúlóng, meaning "Torch Dragon" in Chinese legend. This cosmic dragon was discovered in a patch of sky studied by the JWST PANORAMIC survey. Though just a billion years old, it already has a clear bulge, bright spiral arms, and a well-formed disk stretching over 60,000 light-years. That’s almost the same size as our own Milky Way.

"What makes Zhúlóng stand out is just how much it resembles the Milky Way – both in shape, size, and stellar mass," says Dr. Mengyuan Xiao, the lead author of the study.

Published in the journal, Astronomy and Astrophysics, she and her team found that this galaxy already contains over 100 billion solar masses in stars. That’s massive by any standard. Its spiral arms span 19,000 parsecs, or about 62,000 light-years. Its stellar mass surface density – how tightly packed the stars are – measures almost 10 billion solar masses per square kiloparsec.

Even more surprising is its color. The center glows red, hinting at older stars and low star formation, while the outer disk shows active star-making regions. This pattern, where galaxies grow from the inside out, matches how many modern spirals evolve.

Zhúlóng wasn't even the main target. It was spotted by chance during a wide-field imaging program called PANORAMIC, which scans the sky while JWST looks at other targets. This method, called "pure parallel imaging," lets researchers map huge areas of the cosmos. It’s a smart way to find rare galaxies like Zhúlóng.

Related Stories

"This discovery highlights the potential of pure parallel programs for uncovering rare, distant objects that stress-test galaxy formation models," explains Dr. Christina Williams, one of the survey leads.

Zhúlóng may be the most extreme example yet. Its properties defy expectations. With a star formation rate of only around 66 solar masses per year, it's forming stars more slowly than other galaxies of its size at that time.

That rate is 10 times lower than typical dusty galaxies from that period. Yet somehow, it already reached full size and structure. That means it had to grow rapidly, with about 30% of its available baryons – the normal matter in its dark matter halo – converted into stars. This is 1.5 times more efficient than what we usually see in even the best star-forming galaxies.

Zhúlóng isn’t alone. JWST has shown that early galaxies formed faster and earlier than the previous record-holder for cosmic snapshots, the Hubble Space Telescope, ever revealed. Before JWST, astronomers thought that well-formed disk galaxies like spirals wouldn’t appear until the universe was at least 3 billion years old. Now, they’re seeing disks and even spirals at redshifts above 5. That means they existed when the universe was less than 1.2 billion years old.

Recent studies suggest that about half of galaxies at redshift below 6 already had disk shapes. This is 10 times more than what older models predicted. Some of these even show signs of grand-design spirals, where arms wrap clearly around a central bulge. It used to be thought that these patterns formed only after long periods of calm. But Zhúlóng breaks that idea.

"This discovery shows how JWST is fundamentally changing our view of the early Universe," says Prof. Pascal Oesch, co-leader of the PANORAMIC survey. As new surveys begin and cover even larger areas, researchers expect to find more galaxies like Zhúlóng. These will help test models of galaxy formation, especially how structure and mass build up so quickly.

The JWST has not only detected massive galaxies earlier in time, but it has also shown that they can look very different. Some early galaxies are compact and quiet. Others, like Zhúlóng, are large and bright, with active star-forming disks. This suggests there might be a variety of paths that galaxies can take, depending on their environment and history.

Zhúlóng is more than a distant spiral. It’s a signal that we may need to rethink the timeline of the cosmos. If galaxies can grow this big, this fast, then the processes that build them must be more efficient than we imagined. Either galaxies started forming earlier than we thought, or the ways they gather and use gas are more powerful.

Future observations from JWST and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) will help confirm Zhúlóng's features. They may also show how it formed its stars, what its gas looks like, and whether its spiral arms behave like those in the nearby universe.

Zhúlóng, with its red light and spiral shape, is more than a pretty face. It is a challenge to the theories that say structure takes time. It proves that order can rise from chaos quickly, and that galaxies in the early universe were anything but primitive. As JWST continues its journey, the Torch Dragon lights the way toward a deeper understanding of our cosmic past.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.