New 3D-printable material brings artificial organs one step closer

UVA engineers turn brittle PEG into a soft, stretchable 3D-printable material that could reshape implants and solid state batteries.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

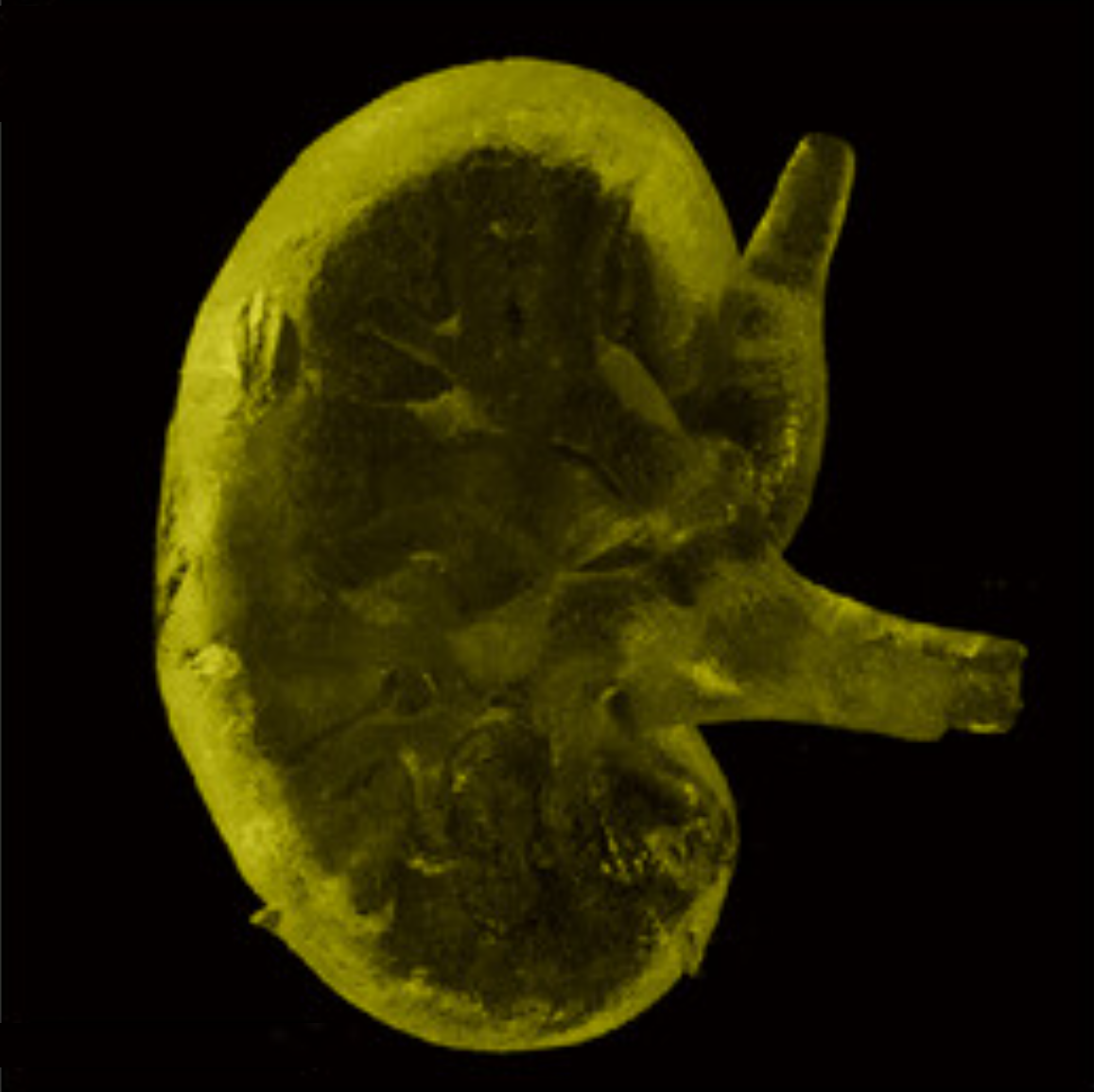

A University of Virginia team has redesigned the common biomedical polymer PEG into a soft, stretchable and 3D-printable material that stays friendly to living cells and even conducts ions, opening new paths for artificial organs, soft implants and flexible solid state batteries. (CREDIT: Advanced Materials)

A new kind of 3D-printable material that can stretch, flex and still stay friendly to living cells could change how medical implants, artificial organs and even batteries are built. Developed by researchers at the University of Virginia, the material begins with something very familiar in medicine, a polymer called polyethylene glycol, or PEG. By redesigning PEG at the molecular level, the team turned a usually brittle substance into a soft, rubbery network that prints like plastic but behaves more like living tissue.

The work, led by Liheng Cai, an associate professor of materials science and engineering and chemical engineering, and first author Baiqiang Huang, a Ph.D. student, is described in the journal Advanced Materials. Their approach shows how tuning the inner “architecture” of a polymer can unlock properties that once seemed out of reach.

Why Regular PEG Was Not Enough

PEG is already a workhorse in biomedical technology. You find it in tissue engineering, drug delivery systems and many other devices that need to coexist with the immune system. It is known to be biocompatible, which means the body usually tolerates it well.

"PEG networks are normally made in water by crosslinking long, linear PEG chains, then removing the water. When the water leaves, the chains pack together, crystallize and turn stiff and fragile. The result is a material that cracks instead of stretches. That is a serious problem if you want to build something that has to bend and move, such as scaffolding for a synthetic organ or a soft device that rests against a beating heart," Cai told The Brighter Side of News.

"Our research group wanted PEG that could keep its good relationship with the body and still act like an elastic band. To get there, we needed to rethink the way PEG molecules are arranged," he continued.

The Bottlebrush Trick

The key idea came from earlier work in Cai’s Soft Biomatter Laboratory. His team had already created very strong synthetic rubbers by storing extra length inside the molecules themselves. They used what is called a foldable bottlebrush design.

In this design, each polymer chain has a central backbone with many side chains sticking out, like bristles on a brush. These bristles can fold and collapse, a bit like an accordion. When the material stretches, those hidden lengths unfold and take the strain. The network becomes both strong and very stretchy without snapping.

“Our group discovered this polymer and used this architecture to show any materials made this way are very stretchable,” Cai said.

Huang took that concept and applied it to PEG. He mixed PEG building blocks into a liquid precursor, then briefly shined ultraviolet light on the mixture. The light triggered polymerization and locked the molecules into a bottlebrush style network. In a few seconds, a runny liquid turned into a soft, flexible solid.

The team produced two kinds of materials this way, PEG-based hydrogels that hold water and solvent free elastomers that stay dry. Both were highly stretchable and could be formed by 3D printing.

Printing Complex, Stretchy Shapes

Because the new PEG mixture responds to UV light, it fits naturally with light based 3D printing. By changing the pattern of the light, the researchers could “draw” almost any structure they wanted inside the liquid, then solidify it.

“We can change the shape of the UV lights to create so many complicated structures,” Huang said. Those structures can be tuned to be either very soft or relatively stiff, but all keep their stretchiness.

For you, that means this is not just a floppy gel in a dish. It is a platform that could be printed into intricate shapes, such as tiny lattices, flexible grids or hollow forms. In the future, that level of control could help build organ like scaffolds with channels for blood flow or devices that bend with muscle and skin.

Playing Nicely With Living Cells

A soft material is only useful in the body if cells accept it. To test that, the team grew living cells alongside samples of the new PEG networks. The cells remained healthy, which showed that the material does not release toxins and does not trigger obvious harm.

The researchers describe the new PEG as “biologically friendly.” For potential implants or tissue scaffolds, that is vital. If you picture a printed support for a future synthetic organ, you need something that stretches like tissue and also lets cells settle, grow and connect. This material moves those goals closer.

Beyond Medicine, Toward Better Batteries

The team also sees promise outside of the clinic. PEG based networks can conduct ions, which makes them interesting for solid state battery electrolytes. Compared to many existing solid polymer electrolytes, the new stretchable PEG materials show higher electrical conductivity and far greater stretchability at room temperature.

“This property highlights the new material as a promising high performance solid state electrolyte for advanced battery technologies,” Cai said. “Our team continues to explore potential extensions of the research in solid state battery technologies.”

Because the network can flex without breaking, a battery built with such an electrolyte might bend with a wearable device or soft robot instead of cracking like hard plastic.

Practical Implications of the Research

This work offers more than a clever chemistry trick. For medicine, a stretchable, 3D-printable PEG network could support the next generation of artificial organs, soft implants and drug delivery systems that move with the body instead of fighting it. Because the material is biocompatible, you could one day see custom printed scaffolds that match a patient’s anatomy and help cells rebuild damaged tissue.

For technology, the same design could lead to safer, more flexible batteries and soft electronics. A stretchy solid electrolyte could reduce the risk of leaks from liquid electrolytes and allow power sources that bend and twist with clothing, wearables or soft robots. That is important if you care about lighter, safer devices that do not shatter when dropped or flexed.

On a broader level, the study shows that carefully tuned molecular architecture can merge things that used to conflict, such as strength and softness or stretch and structure. That lesson may guide future materials that help surgeons, patients, engineers and everyday users by making devices that fit human bodies and human lives more gently.

Research findings are available online in the journal Advanced Materials.

Related Stories

- Major breakthrough unlocks scalable artificial blood production

- PROTEUS System: Artificial biological intelligence to change the future of healthcare

- Self-powered artificial synapse brings human-like vision to smart devices

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Mac Oliveau

Writer

Mac Oliveau is a Los Angeles–based science and technology journalist for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication focused on uplifting, transformative stories from around the globe. Passionate about spotlighting groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, Mac covers a broad spectrum of topics including medical breakthroughs, health and green tech. With a talent for making complex science clear and compelling, they connect readers to the advancements shaping a brighter, more hopeful future.