New tests show Jordan lead codices are not all modern fakes

Ion beam tests show some Jordan lead codices use lead over 200 years old, keeping the debate over their origin alive.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

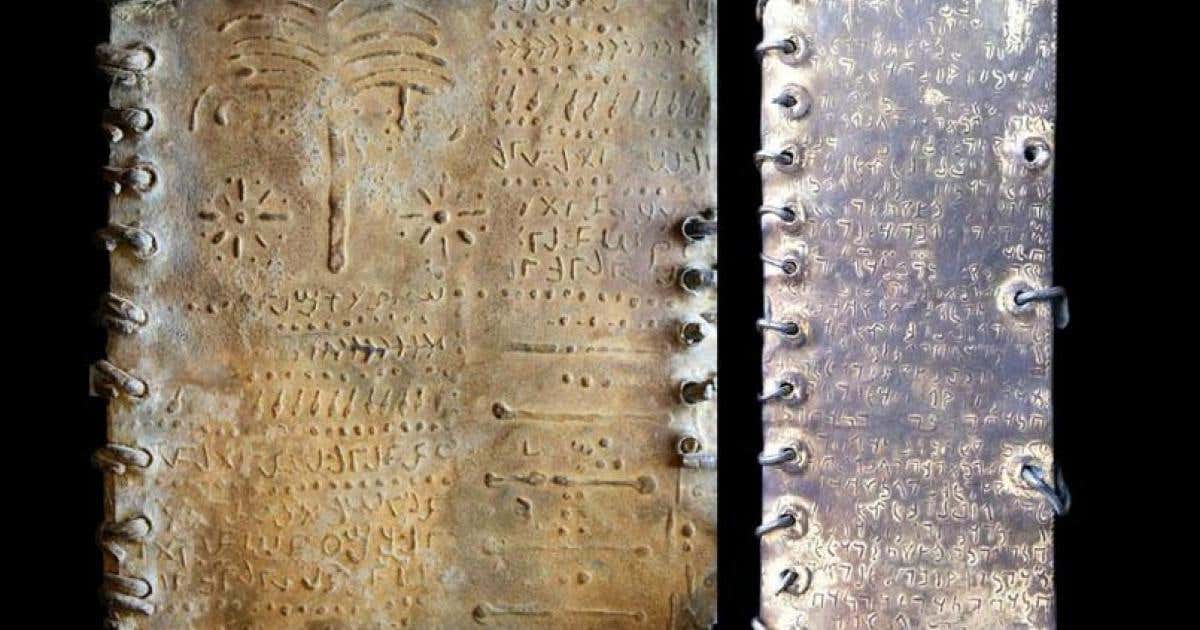

A new ion beam study of the disputed Jordan lead codices finds some pieces made from clearly modern lead and others from metal more than 200 years old, reopening the debate over whether any of these strange little books could be genuinely ancient. (CREDIT: Wikimedia / CC BY-SA 4.0)

For more than a decade, a set of tiny lead books from Jordan has sat in a strange place between wonder and doubt. Some people claimed they might come from the earliest days of Christianity. Many scholars called them outright fakes. Now, after years of argument, a detailed scientific study has taken a hard look at the metal itself and given you a more complex answer than a simple real or fake.

A Controversy That Would Not Go Away

The objects, known as the Jordan lead codices, look like miniature books cast in lead, with pages joined by metal rings. Their surfaces carry symbols, portraits and lines of text that blend several styles. From the start, that mix raised red flags for historians.

The new work does not judge the artwork or the writing. Instead, it asks a simple question that matters to you if you care about evidence: how old is the metal, and can it be clearly linked to modern industry or to much earlier times.

The study, led by Professor Roger Webb at the University of Surrey’s Ion Beam Centre, was published in the journal Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B. Webb has been testing pieces of the codices since 2011. As methods improved, he and his team returned to the problem with sharper tools and a more cautious eye.

Testing Lead At the Atomic Level

To get past opinion and into measurable facts, the researchers used four different techniques on samples from the codices, working with partners in Glasgow, at the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre and at the University of Vienna.

They looked at trace elements in the lead to see which tiny chemical fingerprints were present. They measured lead isotopes, the different atomic versions of the metal that can hint at where the ore was mined. They checked alpha particle emissions, which relate to radioactive decay. Finally, they examined radiogenic helium, a gas that slowly builds up inside lead as other elements break down over time.

No one method could tell you a clean age. Lead is hard to date, and contamination from soil, air and handling can blur the signals. But together, the four approaches let the team compare outer pages, inner sheets and known modern lead in much greater detail than before.

What the Results Actually Say

The clearest message for you as a reader is this: some parts of at least one codex are clearly older than 200 years, and some other pieces appear modern. That mix is exactly what makes the story so tricky.

The study found that several outer pages had so much environmental contamination that any age reading became unreliable. These surfaces seem to have interacted strongly with their surroundings, which scrambled the dating methods. Inside pages, protected from direct contact with air and soil, told a different story. There, the readings were cleaner and pointed to metal that is at least two centuries old, and possibly older.

At the same time, Webb and his colleagues also identified codices that match modern lead. Those objects, in their view, are almost certainly recent. The picture that emerges is not one simple verdict for every piece, but a patchwork.

“Our aim throughout this work has been to bring rigorous, objective science to a subject that has attracted a great deal of speculation,” Webb said. “We have been unable to prove that they are truly ancient, but we have also not been able to prove that all of the objects are modern. We have seen some codices that have tested to be modern, but others clearly test as older than 200 years, thus as far back as our currently successful tests can go.”

Why Lead Is So Difficult To Judge

If you are used to hearing about carbon dating, it may surprise you that metal objects are much harder to pin down. Lead can be melted and reused again and again. Its isotopes can show where it came from, but not the exact date when it was shaped into a book like codex pages.

The Surrey team also had to fight against the non uniform nature of the samples. Different parts of the same codex had different levels of corrosion and outside material mixed in. Those differences changed how helium, alpha particles and trace elements appeared in the measurements. That is why the authors stress that their findings are not the final word on age, but the best snapshot possible with current tools.

A Lab Built For Tiny Clues

The work depended on the Surrey Ion Beam Centre, which runs some of the most advanced ion beam instruments in the United Kingdom. These machines fire beams of charged particles at a sample and then read the signals that come back, down to microscopic and atomic scales.

In other projects, the centre has used similar methods to study timbers from the historic ship Cutty Sark and to help judge whether a painting could truly be linked to Leonardo da Vinci. For the Jordan codices, that same level of fine detail allowed the team to pick apart layer after layer of lead and corrosion.

“At the Surrey Ion Beam Centre, we routinely apply these techniques to everything from quantum devices to cultural heritage objects, and our study shows just how powerful ion beam analysis can be,” Webb said. “The fact that some key samples cannot be shown to be modern provides a strong scientific basis for scholars to take the codices seriously and for further, more advanced testing to be carried out.”

Not Proof, But a New Starting Point

If you hoped this study would finally prove that the Jordan codices are early Christian treasures, you do not get that answer. If you hoped it would expose all of them as twenty first century fakes, you do not get that answer either.

What you do get is a careful scientific argument that the story is more subtle. Some objects really are modern. Others contain lead that looks clearly older than 200 years and does not match standard modern material. Because of contamination and uneven samples, current techniques cannot push much farther back in time.

The project was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 programme and the United Kingdom’s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. The team is now seeking new funding and partners to apply even more sensitive methods and to test more pieces. For now, the codices remain in a gray zone that invites more investigation rather than a final verdict.

Practical Implications of the Research

For historians, this work sends a clear message: you should not dismiss every Jordan codex as a modern fake based only on style or first impressions. Some pieces deserve deeper study, using both scientific tests and careful reading of their symbols and texts.

For scientists, the study shows how powerful combined ion beam, isotope and helium techniques can be when you need to test disputed artifacts. The same toolkit can help you judge other controversial finds, protect cultural heritage, and spot forgeries in art and archaeology.

For the wider public, the research is a reminder that questions about the past are often slow to answer. Careful testing, open data and repeated checks across different labs give you a more honest picture than quick, dramatic claims. As methods improve, the same codices can be revisited, and your understanding of them can change.

In the long run, this kind of work strengthens trust between science and the humanities. It encourages museums, governments and private owners to allow samples from sensitive objects, knowing that the results will add real value, even if they do not solve every mystery at once.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research.

Related Stories

- Scientists just broke a 100-year-old rule in chemistry – it’s time to rewrite textbooks

- Pope Francis and the Vatican just created an “AI Bible” reshaping faith in the Digital Age

- Medieval scholar declared the Shroud of Turin a fake centuries ago

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Rebecca Shavit

Writer

Based in Los Angeles, Rebecca Shavit is a dedicated science and technology journalist who writes for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication committed to highlighting positive and transformative stories from around the world. Her reporting spans a wide range of topics, from cutting-edge medical breakthroughs to historical discoveries and innovations. With a keen ability to translate complex concepts into engaging and accessible stories, she makes science and innovation relatable to a broad audience.