New universal cancer vaccine fights tumors by kickstarting immune defenses

A new mRNA vaccine boosts immune response in resistant tumors, opening the door to a universal cancer immunotherapy.

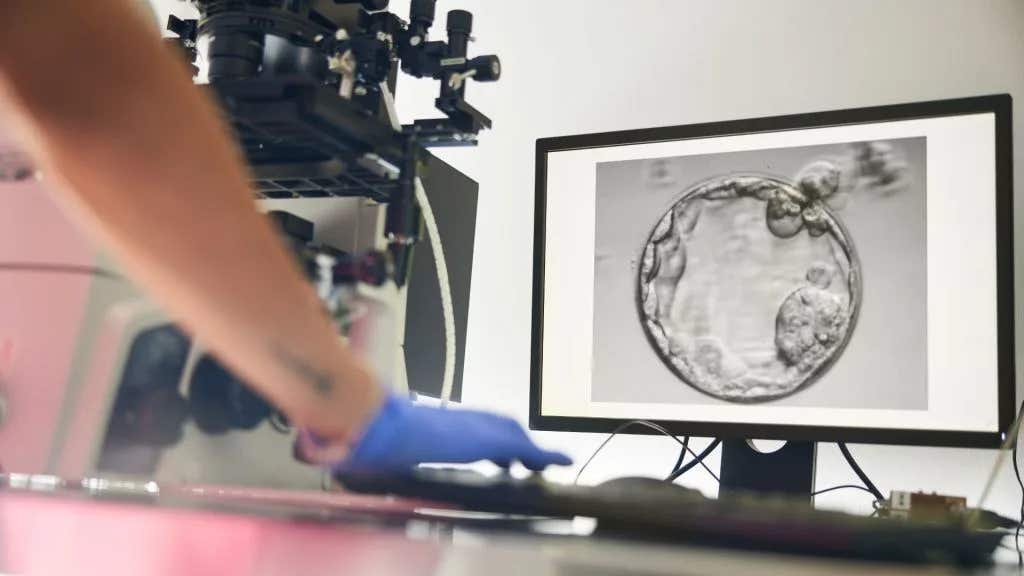

A general mRNA vaccine supercharged the immune system in mouse models, turning resistant cancers into responsive ones. (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 4.0)

Cancer immunotherapy has transformed the treatment landscape by helping the immune system recognize and attack tumors. At the heart of this approach are immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which block pathways that suppress immune activity. These therapies unleash T cells to find and destroy cancer cells.

Yet, success often depends on the cancer's mutational load. Tumors with more genetic mutations typically respond better, since they present more “neoepitopes” — markers that signal the immune system. But some highly mutated tumors still resist ICIs, while others with few mutations occasionally respond.

This puzzle has led researchers to look deeper into what makes certain tumors more visible to the immune system. One focus has been type-I interferons — proteins your body makes when it detects invaders like viruses. These molecules can both help and hinder treatment.

In early stages of therapy, interferons kickstart immune activity, helping T cells recognize and respond to tumors. But when interferons stay active too long, they can lead to chronic inflammation that actually shuts down immune defenses.

A recent study published in Nature Biomedical Engineering offers new insight into how these interferons might be used to boost immunotherapy’s power — not by targeting cancer directly, but by sparking the body’s defense system more broadly. Led by Dr. Elias Sayour at the University of Florida, researchers developed a new type of mRNA vaccine that doesn’t aim at specific cancer markers but instead sends a strong “wake-up” call to the immune system.

A Surprising Strategy: Boosting Without Specific Targets

The approach flips the usual cancer vaccine strategy on its head. Traditionally, scientists have focused on two paths: find a common target shared by many patients, or tailor vaccines for individual tumors. Sayour’s team showed a third path might work — a general mRNA vaccine that simply mimics a viral infection.

Instead of hunting for the right cancer target, they used RNA to produce proteins that mimic infection-related signals. This stirred the immune system to act, creating a chain reaction that made tumors more visible and vulnerable. The treatment wasn’t aimed at specific tumor markers. It didn’t need to be. Just jumpstarting the immune system was enough.

Related Stories

- Breakthrough breast cancer vaccine stops tumors before they start

- Lifesaving new vaccine protects against multiple types of cancer

- Breakthrough mRNA vaccine reinvents pancreatic cancer treatment

The vaccine works by using lipid particles to deliver messenger RNA (mRNA) — the same kind of blueprint used in COVID-19 vaccines — to cells. Once inside, the RNA causes cells to produce certain proteins that activate an immune response. One protein in particular, called PD-L1, showed higher expression inside tumors after the vaccine, making them more susceptible to existing immunotherapy drugs like PD-1 inhibitors.

Turning Resistant Tumors Into Responsive Ones

In animal studies, this strategy proved effective against melanoma — a form of skin cancer — that typically resists immunotherapy. Mice that received the mRNA vaccine along with a PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor showed dramatic immune responses. The tumors not only shrank but, in some cases, disappeared. Even more impressive, the immunity spread to other tumor types and protected the mice from new cancer growth.

The researchers also tested the vaccine on bone and brain tumors. These cancers often have low levels of mutation, making them poor candidates for current immunotherapies. Still, when treated with the vaccine, the mice showed improved survival. In some cases, the vaccine alone — without any additional drugs — was enough to eliminate tumors.

Sayour, a pediatric oncologist and researcher at UF Health, said, “This finding is a proof of concept that these vaccines potentially could be commercialized as universal cancer vaccines to sensitize the immune system against a patient’s individual tumor.”

Duane Mitchell, co-author and co-director of the UF Preston A. Wells Jr. Center for Brain Tumor Therapy, added, “We found that by using a vaccine designed not to target cancer specifically but rather to stimulate a strong immunologic response, we could elicit a very strong anticancer reaction.”

Toward a Universal Cancer Vaccine

The team’s goal is not just to treat cancer but to shift the entire treatment model. Rather than designing vaccines for each tumor type, this strategy offers a potentially universal solution — an off-the-shelf vaccine that could support nearly all cancer patients.

This work builds on Sayour’s earlier human trial, where a personalized mRNA vaccine helped a small group of glioblastoma patients mount a strong immune response. That vaccine was designed from each patient’s tumor. Now, by removing the need for personalization, the team is one step closer to producing a cancer vaccine that could be mass-produced and delivered more easily.

“Taken together, the study’s implications are striking,” said Mitchell. “It could potentially be a universal way of waking up a patient’s own immune response to cancer. And that would be profound if generalizable to human studies.”

Researchers believe the early burst of type-I interferons caused by the vaccine plays a key role in this immune awakening. These interferons seem to help the body expand its immune attack, allowing “epitope spreading,” where the immune system starts to recognize other tumor signals beyond the original target. This self-amplifying process increases the chance of defeating the cancer — even those resistant to earlier treatments.

The Road Ahead

The findings offer new hope for patients whose tumors don’t respond to current therapies. Sayour and his team are now working to refine the vaccine formula and move quickly into human trials. If the vaccine proves effective in people, it could open the door to a future where cancer treatment involves fewer surgeries, less chemotherapy, and broader protection.

The research, supported by the National Institutes of Health and other foundations, represents years of effort at the RNA Engineering Laboratory at UF. Scientists there believe mRNA vaccines could become a cornerstone of cancer care — not just as a personalized tool, but as a powerful general therapy to turn cold, unresponsive tumors into targets the immune system can destroy.

As Aude Craik put it: “This vaccine acts like a new force,” giving even the most stubborn cancers a reason to fear your immune system.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.