Rising temperatures and widespread pollution are making glaciers melt at record rates, study finds

A new study shows glaciers in western Canada, the U.S., and Switzerland lost 12% of their ice since 2021—double the previous rate.

Glaciers in Canada, the U.S., and Switzerland lost 12% of their ice in just four years, driven by heat and wildfire pollution. (CREDIT: Brian Menounos)

Glaciers are vanishing faster than expected across parts of North America and Europe, and the rate of loss is speeding up.

A new study from the Hakai Institute reveals that glaciers in western Canada, parts of the U.S., and Switzerland lost around 12 percent of their ice volume between 2021 and 2024. That’s double the pace of the previous decade. The findings point to a troubling trend: rising temperatures and widespread pollution are making glaciers melt at record rates.

Over just four years, glaciers in these regions lost more than 23 billion metric tons of ice every year. This steep increase in ice loss follows an already sharp rise reported in a 2021 study, which showed that glaciers melted twice as fast between 2010 and 2019 compared to the early 2000s.

The new study builds on that work and gives a clearer picture of how extreme weather, wildfire soot, and desert dust are speeding up the damage.

Rapid Loss Fueled by Heat and Dust

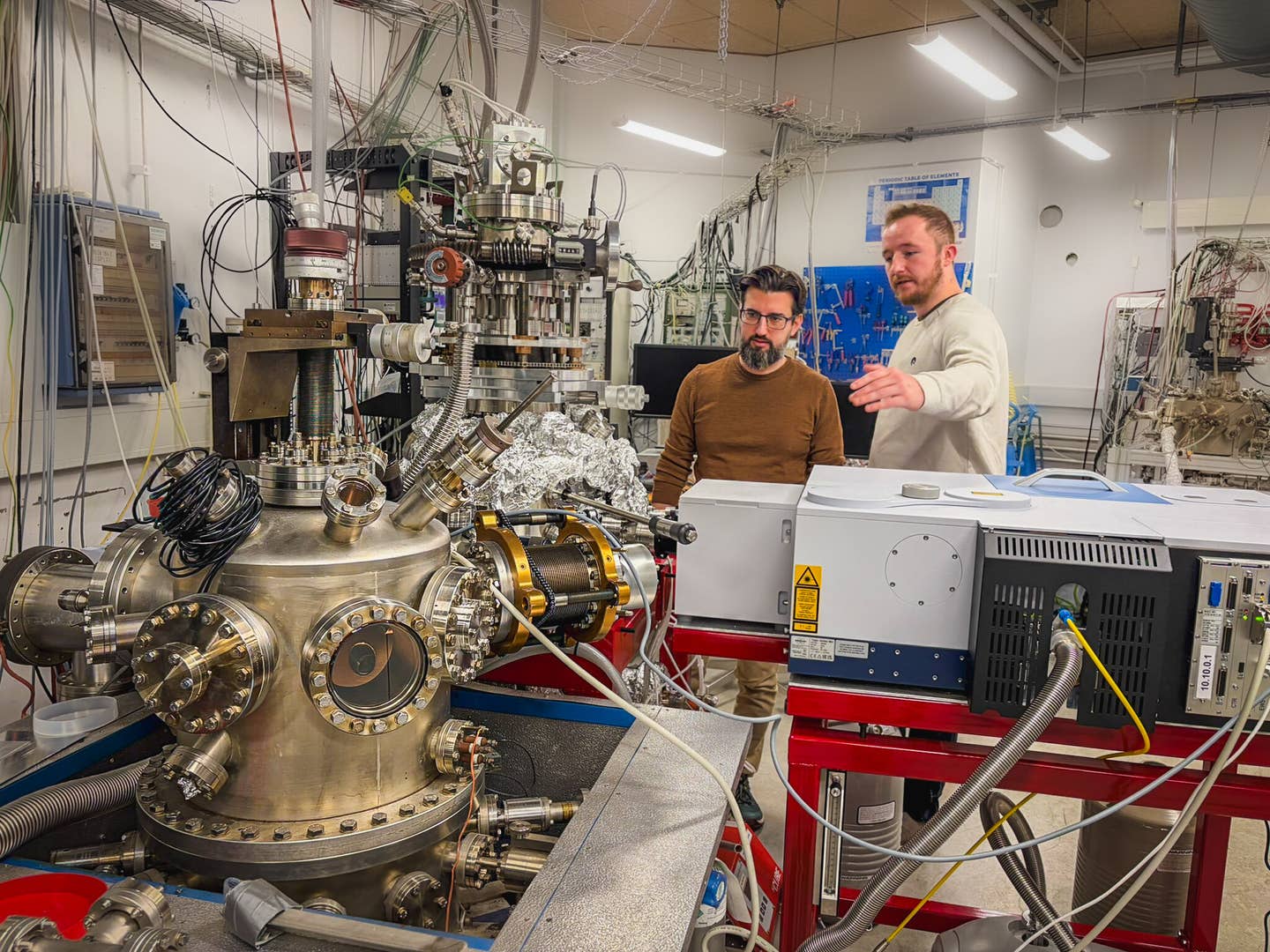

Researchers studied glaciers in western Canada, the U.S. Pacific Northwest, and Switzerland using satellite images, aerial surveys, and on-site observations. Across the board, the cause of melting was clear. A mix of less snowfall, early heat waves, and long dry seasons led to a drop in glacier volume.

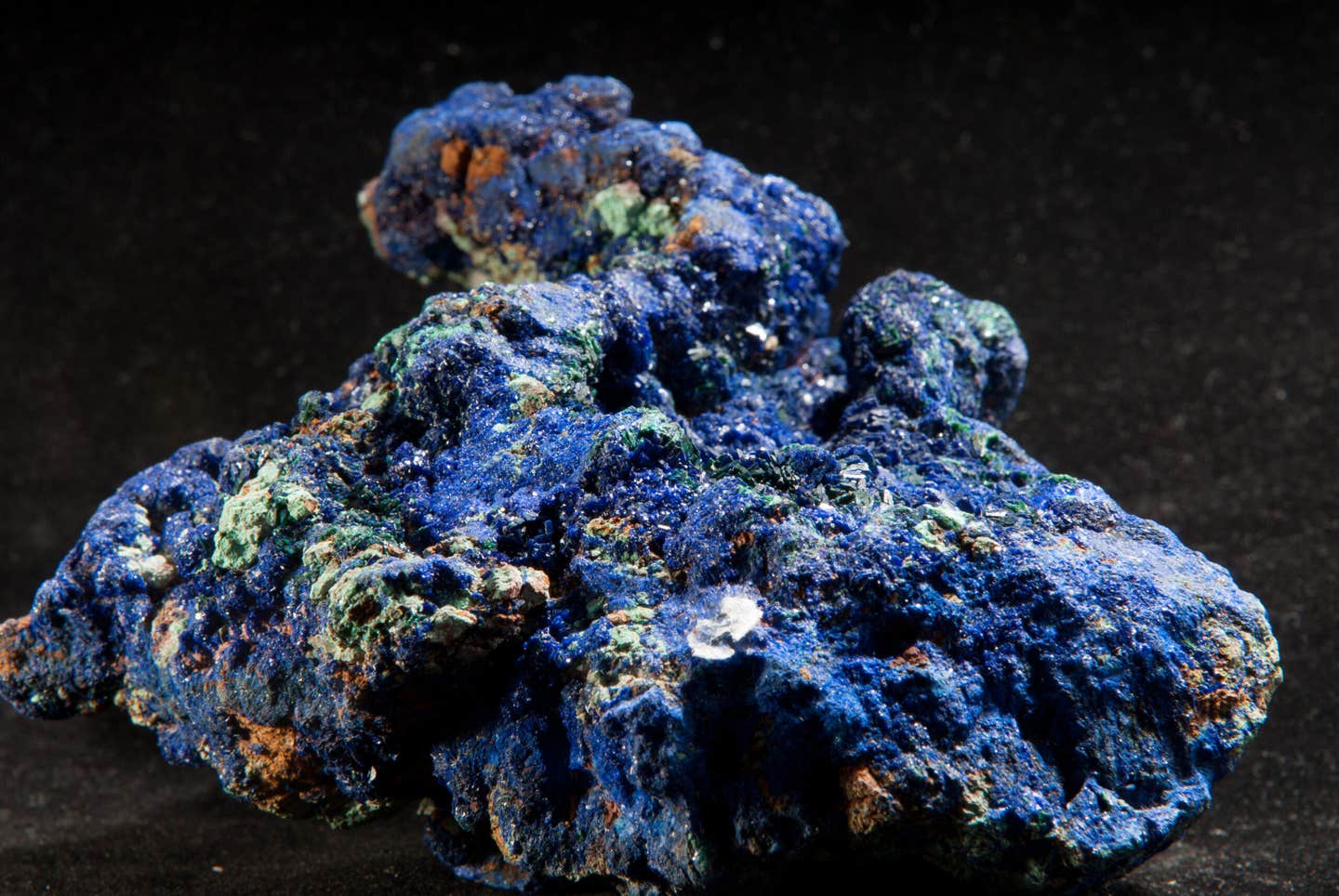

But the weather wasn’t the only problem. Dark particles from wildfires and desert storms fell on the snow and ice, changing their color and making them absorb more heat from the sun. This process, called the ice-albedo effect, lowers the glacier’s ability to reflect sunlight. When snow stays bright and clean, it reflects most of the sun’s energy. When it’s covered in black carbon or dust, it soaks in heat, speeding up the melt.

“In 2023, it was the worst wildfire season in Canadian history,” says Brian Menounos, the study’s lead author and a professor at the University of Northern British Columbia. “That year of record really hit the glaciers hard.”

Related Stories

- Melting ice age glaciers triggered surprising changes deep within Earth

- Buried under 2 kilometers of Antarctic ice, scientists find a 34-million-year-old lost world

In Switzerland, the dust came from across the globe. Winds carried fine sand from the Sahara Desert all the way to the Alps. In Canada and the U.S., the black carbon came from local and regional wildfires. Both types of impurities darkened the glacier surfaces, made them warmer, and caused more melting.

One Glacier Lost 40 Percent of Its Mass to Darkening

At Haig Glacier, located in the Canadian Rockies, researchers found that darkening caused nearly 40 percent of the melting between 2022 and 2023. That’s a shocking amount caused not just by heat, but by what’s falling from the sky.

Scientists say this ice-darkening effect isn’t fully included in many climate models. That means current predictions about glacier loss could be too hopeful. “If we’re thinking, Well, we have 50 years before the glaciers are gone, it could actually be 30,” says Menounos. “So we really need better models going forward.”

The glacier loss in this study won't raise sea levels much. But the local effects are far more serious. Many mountain communities rely on glacier runoff for fresh water during summer and early fall, especially during droughts. When the ice is gone, those water supplies could dry up.

Tourism may also suffer. Glaciers draw people in for hiking, skiing, and sightseeing. Without them, some regions could see a hit to their local economies.

And there’s also a hidden danger: glacial lakes. As glaciers melt, they form lakes held in place by ice or loose rock. These lakes can burst suddenly, causing floods downstream. As glaciers continue to shrink, the risk of these events grows.

Snow Lines Are Rising Higher Each Year

One of the key signs of trouble is the snow line. This is the level on a glacier where snow survives year-round. Researchers found that this line is creeping higher and higher, meaning less snow sticks around to reflect sunlight or build up the glacier again.

In the past, winter snow helped glaciers recover from summer heat. But over the past four years, low snowfall left glaciers exposed. Without fresh snow to cover impurities, dark ice remained bare and continued to soak up the sun’s heat.

That exposed ice not only melted faster but also changed the glacier’s long-term structure. High-elevation areas that once stored firn—a type of compacted snow that eventually becomes ice—have lost this layer. Without it, future snow might not stick and build up into glacier mass. Unless seasonal snow can bury these darker, older surfaces, melting will stay high. Right now, the conditions aren’t helping.

Better Models Are Needed to Predict the Future

The researchers say climate models need to include the physical movement of black carbon and dust through the snow and ice layers. These impurities don’t just sit on the surface; they can move down through the glacier, making their impact last longer than just one melt season.

Models also need to better track firn, the snow layer between fresh powder and hard glacial ice. Firn plays a key role in how much water glaciers can store and how fast they melt. But its ability to absorb water is shrinking along with the glacier itself. Menounos believes that failing to include these fine-scale processes could make predictions less reliable.

“Society needs to be asking what are the implications of ice loss going forward,” he says. “We need to start preparing for a time when glaciers are gone from western Canada and the United States.”

Glaciers are more than just ice. They’re water banks for ecosystems, safety valves for rivers, and cultural landmarks for communities. As the melt speeds up, the time to act is now.

Research findings are available online in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.