Scientists can now 3D print one of the world’s hardest tool materials

Researchers at Hiroshima University developed a laser based 3D printing method that shapes tungsten carbide tools with high hardness and less waste.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

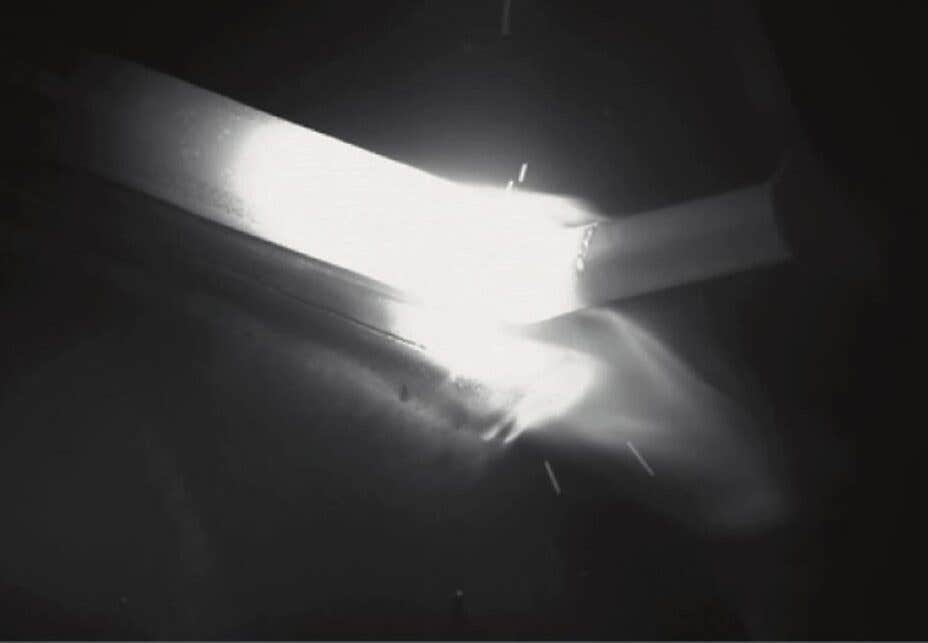

Image taken by a high-speed camera during molding with the rod‑leading method. (CREDIT: International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials)

Hard materials keep modern life moving, from drill bits to cutting tools. One of the toughest is tungsten carbide with cobalt, often shortened to WC–Co. It lasts a long time and resists wear, but shaping it has always been costly and wasteful. That problem may finally have a practical answer.

Researchers at Hiroshima University in Japan report a new way to shape these carbides using additive manufacturing, often called 3D printing. The work was led by Keita Marumoto, an assistant professor in the Graduate School of Advanced Science and Engineering. Their study was published online in the International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials and will appear in the April 2026 print issue.

The team focused on a laser-based process that builds carbide only where it is needed. The goal was to keep the same strength and hardness as traditional parts while cutting waste and cost.

Rethinking how superhard materials are made

WC–Co cemented carbides are common in cutting and construction tools. Their strength comes from tiny grains of tungsten carbide held together by cobalt. Traditional manufacturing presses powders under high pressure and then heats them in large furnaces. The method works well, but it uses a lot of expensive material and struggles with large or complex shapes.

Additive manufacturing offers a different path. Instead of shaping an entire block, material can be placed only on key areas, such as a cutting edge. That idea also allows hard carbide regions to sit on tougher base metals, creating multi material parts.

Making this work has been difficult. Many additive methods rely on powders, which can carry tiny pores and impurities. Laser heat can also break down tungsten carbide, creating weaker phases and defects. Even the best results often fall short of the quality seen in sintered parts.

The Hiroshima University team took a different approach. Instead of powders, they fed solid rods made from sintered WC–Co. These rods already had the right structure and fewer flaws.

Heating without destroying the carbide

The process combines a laser with a hot wire system. Electric current preheats the carbide rod before it reaches the laser. That reduces how much laser energy is needed and limits heat damage.

Two laser strategies were tested. In the first, the rod led the process and the laser hit it directly. This caused trouble. The upper part of the build developed pores and cracks. Tests showed the carbide broke down into unwanted forms, including graphite.

The second strategy put the laser first, aiming it between the rod and the steel base. This avoided direct laser contact with the rod and reduced chemical breakdown. But new problems appeared. Hardness dropped, and iron from the steel base mixed into the carbide layer. The cobalt content also rose, which softened the material.

“Cemented carbides are extremely hard materials used for cutting tool edges and similar applications, but they are made from very expensive raw materials such as tungsten and cobalt, making reduction of material usage highly desirable. By using additive manufacturing, cemented carbide can be deposited only where it is needed, thereby reducing material consumption,” Marumoto said.

A middle layer that makes the difference

To solve the base material problem, the researchers added a thin nickel based alloy layer between the steel and the carbide. This middle layer acted as a buffer. It limited heat flow into the steel and blocked iron from creeping upward.

With this change, the process stabilized. The carbide rod softened instead of decomposing. Tests showed no signs of the damaging phases seen before. Hardness stayed high, reaching about 1400 HV near the surface. That puts it among the hardest industrial materials, just below sapphire and diamond.

Microscope studies also showed the carbide grains stayed small. Some growth occurred, but the structure remained close to the original rod. The cobalt binder did move slightly, yet the change was much smaller than in earlier trials.

“The approach of forming metal materials by softening them rather than fully melting them is novel, and it has the potential to be applied not only to cemented carbides, which were the focus of this study, but also to other materials,” Marumoto said.

What this means for manufacturing

The study shows that high quality WC–Co parts can be built layer by layer without the usual defects. By controlling temperature and using a middle layer, the team avoided carbide breakdown and kept strength intact.

Cracking at the start of some builds remains an issue. The researchers believe better heat control during the process could fix that. They also want to try more complex shapes and explore other material combinations.

If refined, this method could change how cutting tools and wear parts are made. Instead of machining large blocks, manufacturers could print carbide only where it matters most. That would save tungsten and cobalt, both costly and limited resources.

Practical implications of the research

This research points to a more efficient way to use some of the world’s hardest and most expensive materials. By reducing waste, manufacturers could lower costs and lessen demand for mined tungsten and cobalt.

The approach could also allow new tool designs, with hard edges bonded to tough supports.

Beyond carbides, the same softening based technique may help shape other difficult metals, opening new paths in industrial manufacturing.

Research findings are available online in the International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials.

The original story "Scientists can now 3D print one of the world’s hardest tool materials" is published on The Brighter Side of News.

Related Stories

- New 3D printing process creates recyclable plastics that stretch and flex

- AI and nano-3D printing produce breakthrough high-performance material

- 3D printed nanoparticles could create novel shapeshifting materials

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Mac Oliveau

Writer

Mac Oliveau is a Los Angeles–based science and technology journalist for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication focused on uplifting, transformative stories from around the globe. Passionate about spotlighting groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, Mac covers a broad spectrum of topics including medical breakthroughs, health and green tech. With a talent for making complex science clear and compelling, they connect readers to the advancements shaping a brighter, more hopeful future.