Scientists discover 16 giant river networks on ancient Mars where life could have thrived

A new study reveals Mars once hosted massive river systems that may hold clues to ancient life and the planet’s wetter past.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

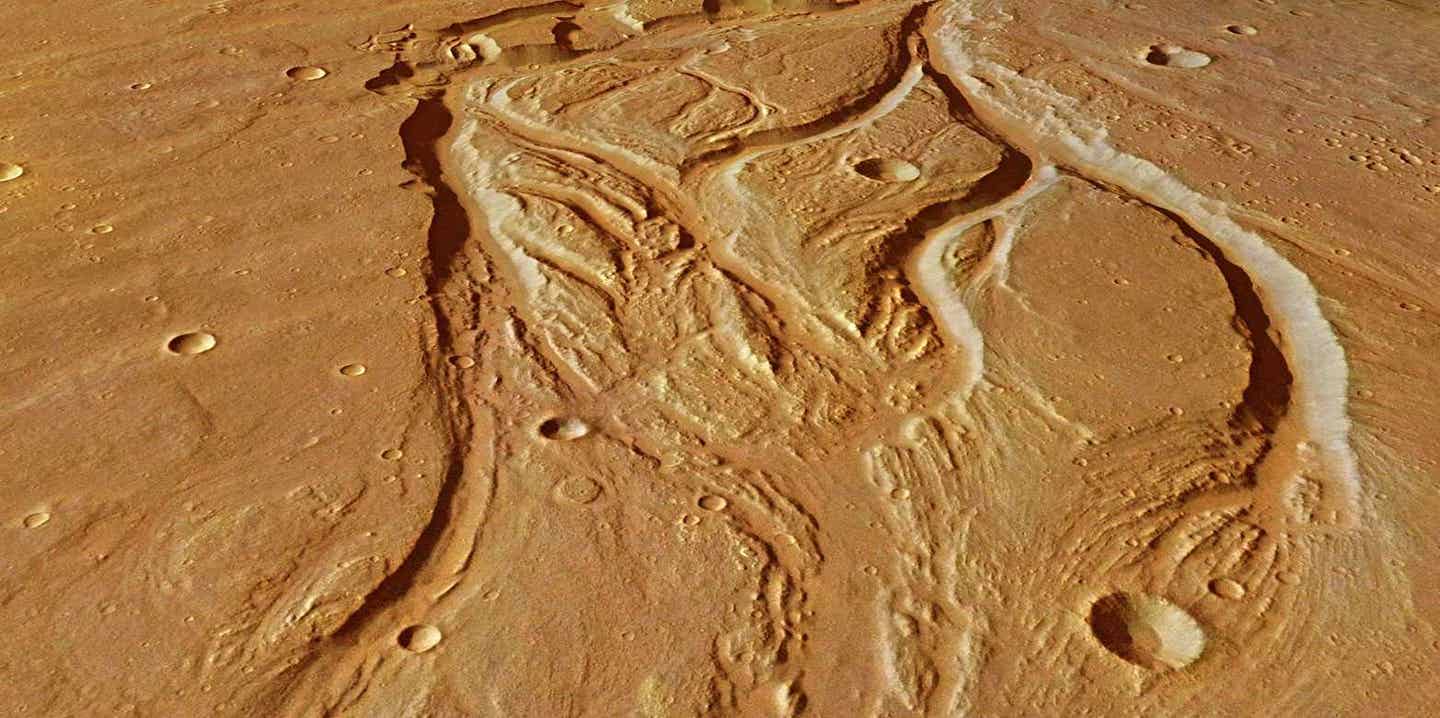

Researchers have identified 16 huge river networks on ancient Mars that carried nearly half of the planet’s sediment and may mark the best places to search for signs of life. (CREDIT: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO)

Long before Mars turned into the frozen desert you see today, water shaped its surface in dramatic ways. Rivers cut through highlands, lakes pooled inside craters, and floods tore open canyon walls. New research shows those waters did not flow randomly. They formed organized river networks across wide regions, similar in scale to Earth’s major watersheds, even though Mars never had moving tectonic plates like our planet.

For years, scientists knew Mars had streams and lakes. What they did not know was whether those pockets of water ever joined into large river systems. A new study published in PNAS answers that question with a striking yes. Researchers from The University of Texas at Austin report that early Mars hosted 16 large river drainage systems, areas where many smaller waterways fed into bigger channels across vast land regions.

A Planetwide Search for Lost Watersheds

To uncover Mars’ ancient plumbing, researchers gathered detailed maps of the planet’s old valleys, lake beds, flood channels, and river deposits. They examined images and elevation data from orbit, tracing how water once moved across the land. Instead of letting a computer draw drainage lines, the team mapped each system by hand. Mars has been pummeled by impacts, reshaped by wind, and covered by volcanic rock. Those changes confuse automated tools. Human eyes were needed.

The group started with 19 possible river basins. Three turned out to be too small. That left 16 that each covered at least 100,000 square kilometers, the same standard used to define major watersheds on Earth. By comparison, Earth has 91 drainage areas that large. The Amazon basin alone covers more than 6 million square kilometers.

Mars’ networks were smaller and rarer. Still, their influence was huge.

Small Area, Huge Impact

Together, the 16 systems covered about 4 million square kilometers. That sounds vast, yet it made up just 5 percent of Mars’ oldest terrain. Despite covering so little ground, those areas carved nearly half of the planet’s river sediment. The team estimates that the big watersheds moved about 28 trillion cubic meters of material, 42 percent of all sediment carried by rivers on ancient Mars.

In other words, a small slice of the planet did nearly half the work.

Within those systems, the channels were tightly packed. The network density was almost seven times higher than in the rest of Mars’ ancient terrain. Outside the grandes rivers regions, most waterways were short and isolated. They often ended in crater basins that trapped water and mud.

Inside the large systems, flows were different. Streams connected to other streams, which fed lakes, which eventually broke through crater walls in violent floods. Those breakouts carved deep canyons and opened pathways for water to travel farther.

Floods That Built the Networks

One type of feature played a major role: outlet canyons. These formed when crater lakes overflowed and burst through their rims. The resulting floods were extreme, capable of scouring bedrock and moving enormous loads of rock and soil.

Nearly half of all known outlet canyon length sits inside the large drainage systems. Within those watersheds, flood-carved channels produced about 41 percent of all sediment. Across the whole planet, they account for just 24 percent. That contrast reveals how important sudden, powerful floods were in stitching together local streams into longer routes.

“These floods helped break the tendency of craters to trap water,” said co-author Timothy A. Goudge, an assistant professor at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences. “They turned closed basins into pieces of longer river paths.”

Postdoctoral fellow Abdallah S. Zaki, who led the work, described the approach in simple terms. “We did the simplest thing that could be done. We just mapped them and pieced them together,” he said.

Where Did All the Mud Go?

If these river systems moved so much material, where did it end up? Some answers are clear. Others remain a mystery.

The team found likely ties between several of the major watersheds and known sediment basins, including regions called Aeolis Dorsa, Arabia Terra, and Hypanis. In a few places, you can trace channels directly into deposits such as fan-shaped piles of sediment. In many others, the link is less certain.

About 21 percent of all river-carried sediment appears to have been delivered to large basins tied to these drainage systems. The rest may be buried deep in impact basins like Hellas or Argyre, or smeared along the edge between Mars’ southern highlands and northern lowlands. Much of it may also be hidden beneath dunes, dust, and lava.

Rivers Without Tectonic Plates

On Earth, mountain building guides rivers. Tectonic plates push land up and pull it down, shaping the routes water follows. Mars never had that kind of activity. Yet it still formed large watersheds.

The researchers say early Mars relied on a different recipe: an uneven surface, rainfall or snowmelt, lakes inside craters, and time. When enough water collected, pressure broke crater walls. That single moment could reorganize miles of terrain.

This matters beyond Mars. If a planet can form major river systems without plate motion, then other worlds might, too, as long as they have water, slopes, and long periods for erosion to work.

Clues to Life’s Chances

Big rivers on Earth support big ecosystems. They move nutrients, mix minerals, and offer stable habitats. The same may have been true on early Mars.

Because sediments from large systems traveled long distances, water had more time to react with rock. Those reactions can produce chemicals that energy-hungry microbes might use. The long journeys also mean sediments were mixed from different terrains, which could trap a record of past environments.

“Since sediment contains nutrients, these are the best spots to look for signs of past life,” Zaki said. “The longer the distance, the more you have water interacting with rocks, so there’s a higher chance of chemical reactions that could be translated into signs of life.”

The study suggests many locations once could have supported life. Still, those 16 big basins may offer the best chances to find clear evidence.

“It’s a really important thing to think about for future missions and where you might go to look for life,” Goudge said.

Department chair Danny Stockli praised the work from the UT team. “Tim Goudge and his team continue to be leaders in the field, making groundbreaking contributions to the understanding of Mars’ planetary surface and hydrologic processes,” he said.

What Remains Uncertain

The researchers stress that their maps are conservative. Impacts and erosion likely erased many channels. Some estimates suggest half of Mars’ original river features vanished over time. The true size of ancient watersheds could be much larger than what appears today.

Another problem is age. Some deposits formed early, others later. Untangling that timeline will take future missions and better dating methods.

Even so, the message is clear. Mars once had more than scattered streams. It had organized river systems powerful enough to reshape the planet. Those lost rivers now point to the places where secrets of another world’s climate, and possibly life, still wait beneath the dust.

Practical Implications of the Research

This research narrows the search for signs of life on Mars. Instead of scanning the entire planet, scientists can focus on the 16 large drainage systems where nutrients and minerals once concentrated. Future rovers and landers can target these regions to look for chemical traces of ancient organisms.

The work also helps predict where underground water or buried sediments might still exist. Beyond Mars, the findings guide how scientists study water on other rocky planets.

Any world with slopes and rainfall could form large rivers, even without plate movement. That broadens the kinds of planets that may support life and shapes how future space missions choose where to explore.

Research findings are available online in the journal PNAS.

Related Stories

- Martian dust storms crackle with 'mini lightning,' revealing a hidden electric Mars

- NASA orbiter data challenges the idea that liquid water exists on Mars

- UC Berkeley and NASA prepare twin satellites — could rewrite what we know about Mars

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.