Walkable cities make you healthier: surroundings make a big difference

Walking more starts with where you live. New research shows moving to a walkable city adds over 1,000 daily steps.

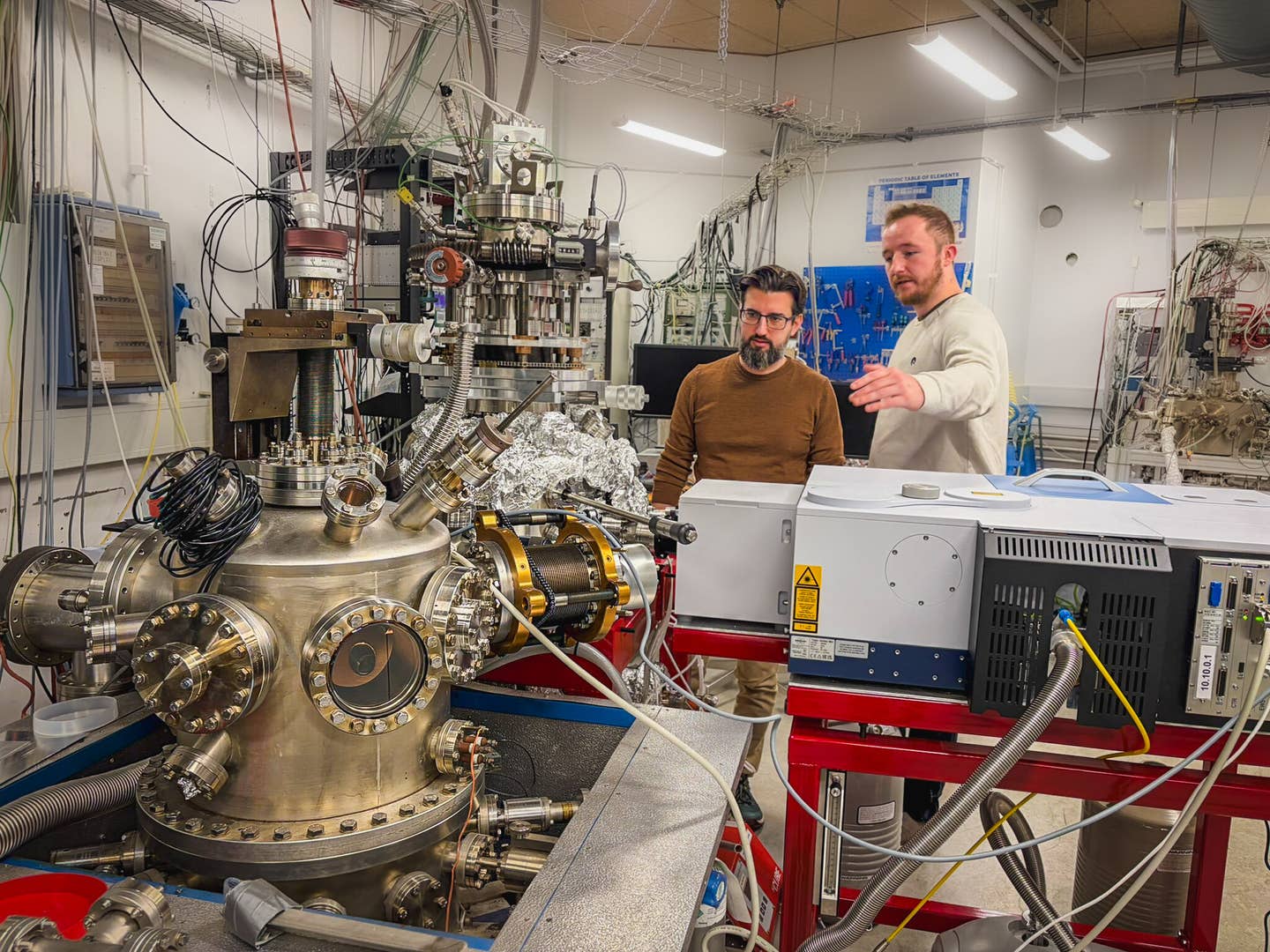

A major study from the University of Washington shows that moving to a more walkable city can increase daily steps by over 1,000, proving city design has a strong effect on health. (CREDIT: Shutterstock)

The way cities are designed affects more than just how long your commute is. It can shape how much you move each day—and how healthy you are. In a new study from the University of Washington, and published in the journal, Nature, researchers found that moving to a more walkable city can significantly boost your daily steps. This matters because walking—even just a little more—has a big effect on your health.

For years, researchers have tried to understand if walkable places cause people to walk more, or if people who like walking just choose to live in those areas. Now, with a huge dataset of real-life step counts, the evidence points clearly in one direction: your surroundings make a real difference.

The findings are especially important as cities continue to grow. Over two-thirds of the world’s population—around 6.7 billion people—are expected to live in urban areas by 2050. If these areas aren’t designed with walking in mind, the health impacts could be major. Inactivity is already a serious global problem, tied to conditions like heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

But this study shows that better infrastructure can help. It’s not just about motivation or willpower. The environment you live in changes how much you walk—without even trying.

From New York to Everywhere

To get strong evidence, researchers from the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering at the University of Washington analyzed detailed data from 5,424 people who had moved at least once between 2013 and 2016. These participants were part of a much larger group of 2.1 million users of the Argus step-counting app. The study only included people who stayed at their new location for at least three months.

Each person’s steps were tracked minute-by-minute for 90 days before and after their move. That adds up to over 248,000 days of step data. Importantly, the researchers filtered out days with extreme counts—fewer than 500 steps or more than 50,000—and avoided counting days around the actual move to reduce skewed results.

They used a system called the Walk Score to measure the walkability of each city. Scores range from 0 to 100 and represent how easy it is to reach places like grocery stores, schools, or parks on foot. Seattle, for example, has a score of 74, meaning it’s “very walkable.”

Related Stories

- A wearable smart insole can track how you walk, run and stand

- New research links changes in walking patterns to early Alzheimer’s

One of the clearest findings came from people who moved to or from New York City, which has a high Walk Score of 89. When 178 people moved to New York from less walkable cities—where the average score was around 48—their average daily steps jumped by 1,400. That’s an increase from 5,600 to 7,000 steps a day. And when people left New York for less walkable areas, they dropped about 1,400 steps per day.

Across all moves, any change in Walk Score of more than 48 points—up or down—resulted in a daily step difference of about 1,100. Moves between cities with similar scores showed no major change in activity.

These patterns held true regardless of age, gender, or weight. The effect wasn’t just about young, fit people walking more. It affected everyone.

Why It Matters

Walking doesn’t have to mean long hikes or intense workouts. Even modest walking is tied to better health. A 2023 global study found that walking just 4,000 steps a day was enough to lower the risk of death from all causes. That’s right around the U.S. daily average—4,000 to 5,000 steps.

But the real benefit comes with doing a little more. For every additional 1,000 daily steps, the risk of death drops by about 15%. That’s huge for something as simple as walking more throughout the day.

The University of Washington study also looked at how walkability affected moderate-intensity walking—defined as 100 to 130 steps per minute. People who moved to areas with Walk Scores that increased by more than 49 points were twice as likely to get at least 150 minutes of aerobic activity per week. That’s the weekly minimum recommended by health experts.

So, how does a city make walking easier? It comes down to thoughtful design. Safe sidewalks, shaded paths, nearby shops, and public transit all play a role. These features don’t just make life more convenient—they help you build better habits without thinking about it.

Real Science, Real Lives

One reason this study stands out is the scale. Past research often struggled with small groups or biased data. Many studies relied on self-reported activity, which can be inaccurate. Others didn’t track people over time, making it hard to know what caused what.

But smartphones changed everything. Today, millions of people carry around devices that track movement and location all the time. These tools provide a window into daily behavior in the real world, not just the lab.

Still, no data set is perfect. As lead author Tim Althoff pointed out, “No data set is truly representative of the whole U.S. population.” Everyone in this study had downloaded a fitness app, which may mean they were already more interested in health than average. But the scale and diversity of the sample still made the results unusually strong.

“Our study shows that how much you walk is not just a question of motivation,” Althoff explained. “There are many things that affect daily steps, and the built environment is clearly one of them.”

He added, “There’s tremendous value to shared public infrastructure that can really make healthy behaviors like walking available to almost everybody, and it’s worth investing in that infrastructure.”

City planners and public health experts agree. As more people live in cities, those cities must be designed to support everyday activity. That means more than just building parks—it means planning neighborhoods that encourage walking as a normal part of life.

And it’s not just about physical health. Other studies show that walking improves mood, reduces stress, and even boosts creativity. Movement is one of the most natural things the human body can do. When cities make it easier, everyone benefits.

The Road Ahead

This new research sends a clear message: your zip code shapes your steps. If your environment makes walking easy and enjoyable, you’re likely to do more of it. If it doesn’t, you may move less—whether you want to or not.

That means public policies around zoning, transit, and infrastructure have real health consequences. If leaders invest in sidewalks, lighting, and mixed-use neighborhoods, they’re also investing in healthier, longer lives for their citizens.

The built environment doesn’t just influence how cities look—it changes how people live.

As more studies harness the power of smartphone data, the picture will only become clearer. For now, one thing is certain: building walkable cities is one of the simplest, most effective ways to support public health.

And it all starts with a single step.

Note: The article above provided above by The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.