Why triceratops and other horned dinosaurs evolved such massive noses

A new reconstruction shows Triceratops’ huge nose likely helped regulate heat and moisture, not just smell.

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

Edited By: Joseph Shavit

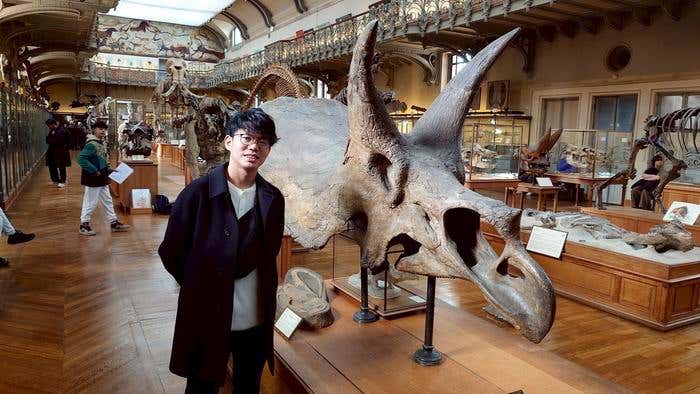

Seishiro Tada (left) standing next to an awe-inspiring Triceratops skull, with its enormous nasal cavity visible at the front. (CREDIT: 2026 Tada et al. CC-BY-ND)

The skull of Triceratops looks almost exaggerated, as if someone enlarged the front half without adjusting the rest. Paleontologists have long studied its horns and frill, yet the cavernous nasal region remained harder to explain. A new reconstruction suggests that space was not empty decoration. It likely housed a complex system for airflow, blood circulation, and temperature control.

Researchers led by Project Research Associate Seishiro Tada of the University of Tokyo Museum examined fossil skulls using high-resolution CT scans and comparisons with living reptiles and birds. By tracing canals inside the bone, they reconstructed where nerves, blood vessels, and soft tissues would have been located. Their work offers the first detailed hypothesis of nasal anatomy in horned dinosaurs, also known as ceratopsids.

“I have been working on the evolution of reptilian heads and noses since my master's degree,” Tada said. “Triceratops in particular had a very large and unusual nose, and I couldn’t figure out how the organs fit within it even though I remember the basic patterns of reptiles. That made me interested in their nasal anatomy and its function and evolution.”

A puzzle hidden inside bone

Ceratopsids were among the most diverse dinosaur groups in the Late Cretaceous. Their skulls rank among the most elaborate structures seen in vertebrates, with beaks, horns, frills, and large nasal openings. Previous studies explored the function of horns and frills extensively. The nasal region, despite its size, remained poorly understood.

To investigate, the team scanned a well-preserved Triceratops prorsus premaxilla collected from the Hell Creek Formation. The fossil was digitally segmented using imaging software, allowing researchers to visualize internal chambers and canals in three dimensions. They then compared those structures with anatomical patterns in modern reptiles, birds, and crocodilians using the Extant Phylogenetic Bracket approach, which infers soft tissues from living relatives.

The results showed that Triceratops had an unusual arrangement of nerves and blood vessels. In most reptiles, sensory and vascular pathways reach the nose partly through the jaw. In Triceratops, skull shape blocked that route. Instead, nerves and vessels traveled primarily through the nasal branch.

“Triceratops had unusual ‘wiring’ in their noses,” Tada said. “In most reptiles, nerves and blood vessels reach the nostrils from the jaw and the nose. But in Triceratops, the skull shape blocks the jaw route, so nerves and vessels take the nasal branch.”

He realized this while assembling 3D-printed skull sections. “I came to realize this while piecing together some 3D-printed Triceratops skull pieces like a puzzle,” he said.

A nerve system unlike other reptiles

The reconstruction suggests the lateral nasal nerve supplied much of the front of the snout, replacing the role usually played by another branch in reptiles. That shift appears linked to evolutionary enlargement of the nostril region. As the naris expanded and bones changed shape, the original nerve pathway became less practical.

Endocast evidence from ceratopsid braincases supports this interpretation. The ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve appears unusually large compared with related species such as Protoceratops, indicating greater functional importance in horned dinosaurs.

Researchers also proposed that blood vessels followed similar pathways, since arteries and veins often run alongside nerves in reptiles. A dense vascular network inside the nasal cavity would have supported heat exchange, a possibility raised in earlier work but not mapped in detail until now.

Evidence for a turbinate structure

One of the most intriguing findings involves a structure called a respiratory turbinate. These thin, curled tissues inside the nose increase surface area, helping regulate temperature and moisture during breathing. They are common in mammals and birds but rarely identified in non-avian dinosaurs.

The team identified a ridge inside ceratopsid nasal bones that closely matches attachment sites for turbinates in birds. Although not all horned dinosaurs show clear evidence, related species in the centrosaurine subgroup possess similar ridges and a projecting narial spine that may have supported the structure.

“Although we’re not 100% sure Triceratops had a respiratory turbinate, as most other dinosaurs don’t have evidence for them, some birds have an attachment base (ridge) for the respiratory turbinate and horned dinosaurs have a similar ridge at the similar location in their nose as well,” Tada said. “That’s why we conclude they have the respiratory turbinate as birds do.”

If confirmed, ceratopsids would represent only the second known group of non-avian dinosaurs with clear turbinate evidence, after pachycephalosaurs.

Cooling a giant head

The researchers propose that these nasal adaptations played a major role in thermoregulation. Large ceratopsid skulls contained substantial tissue mass around the brain and sensory organs, which would have generated heat. Efficient cooling would have been essential.

Previous studies suggested the nasal region acted as a heat-exchange site in dinosaurs. The new reconstruction strengthens that idea by identifying vascular pathways and potential turbinate structures that would increase airflow surface area. Together, these features could have cooled blood before it reached the brain and eyes.

Even if Triceratops was not fully warm-blooded, maintaining stable head temperatures would still have been beneficial.

Filling a missing piece

Horned dinosaurs were the last major dinosaur group lacking detailed nasal soft-tissue reconstruction. This study aims to close that gap by proposing locations for nerves, blood vessels, nasal glands, and ducts.

“Horned dinosaurs were the last group to have soft tissues from their heads subject to our kind of investigation, so our research has filled the final piece of that dinosaur-shaped puzzle,” Tada said. He plans to explore other skull regions next, including the distinctive frill.

The authors note limitations. Some structures lack clear bone evidence, and certain features, such as pneumatic sinuses, remain uncertain. Inferences rely on comparisons with living animals, which introduces unavoidable uncertainty.

Still, the work provides a framework for understanding how ceratopsid skull anatomy functioned in life rather than just how it looked.

Research findings are available online in the journal The Anatomical Record.

The original story "Why triceratops and other horned dinosaurs evolved such massive noses" is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Related Stories

- The surprising role of baby dinosaurs within the Jurassic food chain

- Decades old T. rex debate ends with stunning discovery

- Dinosaurs thrived until the end: New Mexico fossils rewrite extinction story

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Mac Oliveau

Writer

Mac Oliveau is a Los Angeles–based science and technology journalist for The Brighter Side of News, an online publication focused on uplifting, transformative stories from around the globe. Passionate about spotlighting groundbreaking discoveries and innovations, Mac covers a broad spectrum of topics including medical breakthroughs, health and green tech. With a talent for making complex science clear and compelling, they connect readers to the advancements shaping a brighter, more hopeful future.