Supercomputer simulations reveal why some black holes shine and others stay dim

New supercomputer simulations show how black holes eat, glow, and launch jets, explaining strange cosmic objects seen by today’s telescopes.

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

Edited By: Joshua Shavit

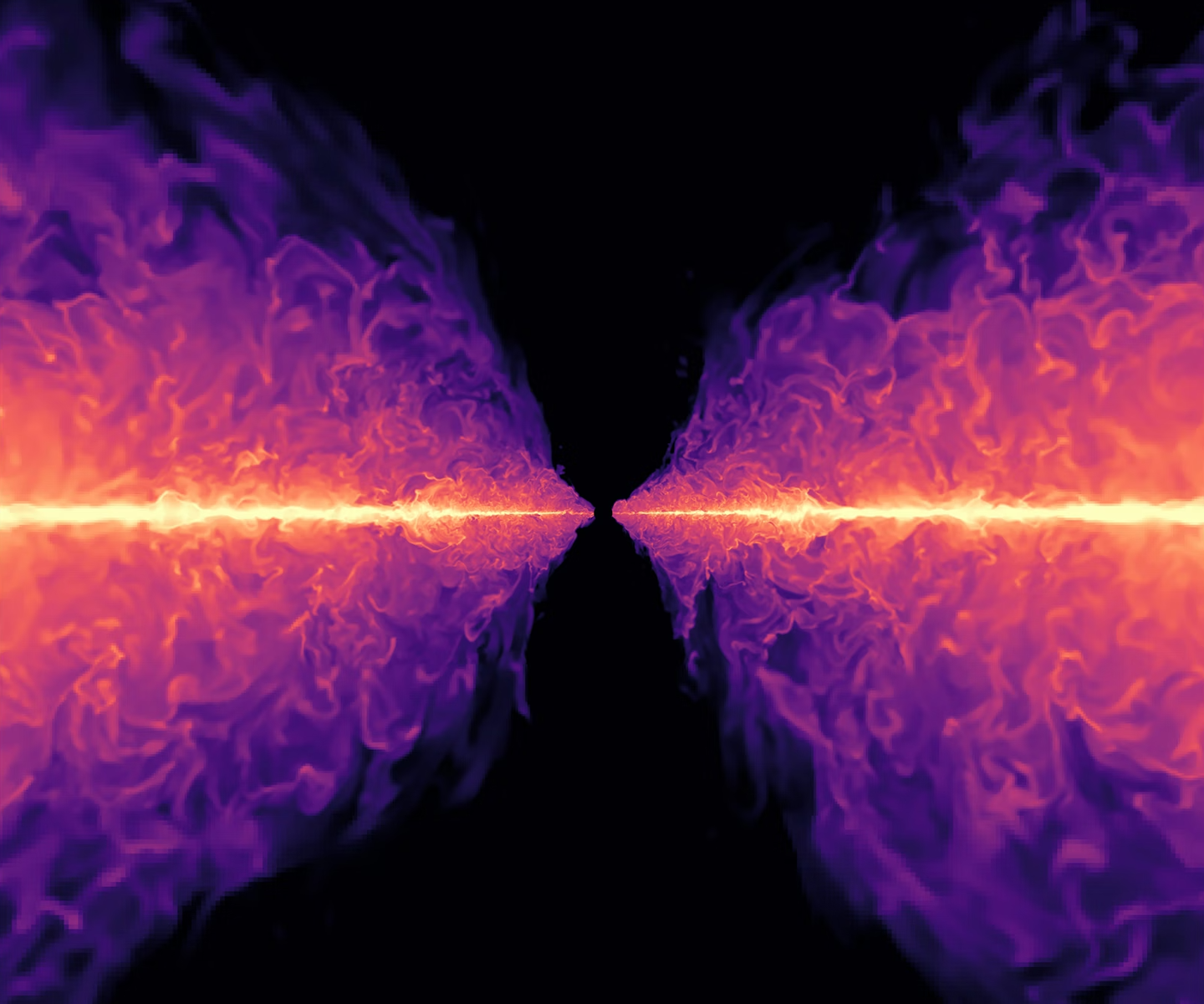

New exascale simulations track light and matter around black holes in full gravity, revealing why some glow, some blast jets, and others hide their shine. (CREDIT: L. Zhang et al.)

Some of the brightest beacons in the universe share one hidden engine: matter falling into a black hole. As gas whirls inward, it heats up and shines. In some cases, it also blasts narrow beams of particles into space. For years, scientists tried to mimic this dance using rough shortcuts. Now, a new study offers the most lifelike view yet of how black holes feed and glow.

The work, published in The Astrophysical Journal, uses supercomputers to track gas, magnetic fields, gravity and light at the same time. The team followed light as it bends through warped space, just as Albert Einstein predicted. The result is a virtual laboratory that behaves like the real sky.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to see what happens when the most important physical processes in black hole accretion are included accurately,” said Lizhong Zhang, lead author and a research fellow at the Simons Foundation’s Flatiron Institute. “Any oversimplifying assumption can completely change the outcome. What’s most exciting is that our simulations now reproduce remarkably consistent behaviors across black hole systems seen in the sky, from ultraluminous X-ray sources to X-ray binaries. In a sense, we’ve managed to ‘observe’ these systems not through a telescope, but through a computer.”

Why light changes everything near a black hole

When matter falls toward a black hole, gravity pulls inward. At the same time, energy from heated gas pushes outward as light. In bright systems, that push can rival gravity. Older models often treated light like a smooth fluid or let it stream freely with few collisions. Those choices made the jobs easier for computers, but they bent the truth.

Zhang and his colleagues built algorithms that solve for light in full detail, inside Einstein’s gravity. The code keeps track of how light scatters, heats gas and escapes or gets trapped. “Previous methods used approximations that treat radiation as a sort of fluid, which does not reflect its actual behavior,” Zhang said.

Making this work demanded muscle. The team ran its code on Frontier and Aurora, exascale machines at Oak Ridge and Argonne national labs. One set of runs alone took about 120,000 hours. Even the shortest attempts still needed thousands.

Christopher White of the Flatiron Institute and Princeton University led the design of the light-tracking engine. Patrick Mullen of Los Alamos National Laboratory optimized it to run at vast scale. The foundation came from earlier work by Yan-Fei Jiang, whose method blends spinning gas and magnetic fields with careful handling of light.

Many black holes, many lifestyles

The team did not study only a single setup. It modeled black holes about ten times the sun’s mass and fed them at wildly different rates. Some took in material far below a theoretical balance called the Eddington limit. Others gulped matter near that line. The most extreme cases pushed more than 100 times that rate.

They also varied spin and magnetic layouts. Spin matters because it twists magnetic fields. Two spin speeds were tested, one modest, one fast. The researchers also tried different magnetic loop patterns inside the swirling disk.

Ten full simulations ran long enough to settle into stable behavior. Then the team measured thickness, glow, winds and jet strength.

What emerged was a family portrait, not a single face.

At very high feeding rates, disks swelled into thick, puffy shapes. Radiation pressure pushed gas into wide outflows that looked more like inflated doughnuts than slim rings.

Near the Eddington balance, the story changed. Disks thinned at their centers and grew a magnetized “atmosphere” called a corona. In those systems, heat sat mostly in magnetic fields.

At the lowest rates, disks became thin and calm. They resembled textbook sketches.

Another surprise: the feared meltdown never came. Older ideas predicted that disks full of radiation should tear themselves apart. Instead, magnetic turbulence steadied the flow and kept the system from overheating.

Brightness has limits you can’t see

One of the strongest lessons is about efficiency. When a black hole feeds slowly, about 5 percent of the incoming energy becomes light. As the pace rises, that share falls sharply. In the wildest runs, less than half of one percent escaped as glow.

So why do some black holes not blaze as bright as expected? The simulations show that much energy gets trapped and dragged inward. In these systems, effort leaves mostly as winds and jets, not light. In a few cases, moving matter carried more energy than radiation by a factor of three or more.

Jets only appeared when strong vertical magnetic fields were present. Fast spin made them fiercer. Some simulated jets raced away at speeds well above what is needed to break free from a black hole’s pull. Systems without sturdy magnetic structure stayed quiet.

This helps explain why some black holes roar in radio waves while others whisper. The difference may lie less in diet and more in magnetic wiring.

Flicker, beams and “little red dots”

Astronomers also care about how often a black hole’s light flickers. The models show that brightness swings depend on feeding rate and magnetic order. Near the Eddington line, poorly ordered fields led to wild changes. Better-organized systems stayed steady.

Light also does not leave these systems evenly. In the highest-feeding cases, a narrow tunnel formed over the black hole. Light escaped mainly through that funnel. If Earth sat inside the beam, the object would look far brighter than it truly is. This may explain ultraluminous X-ray sources, which could be ordinary systems seen from a lucky angle.

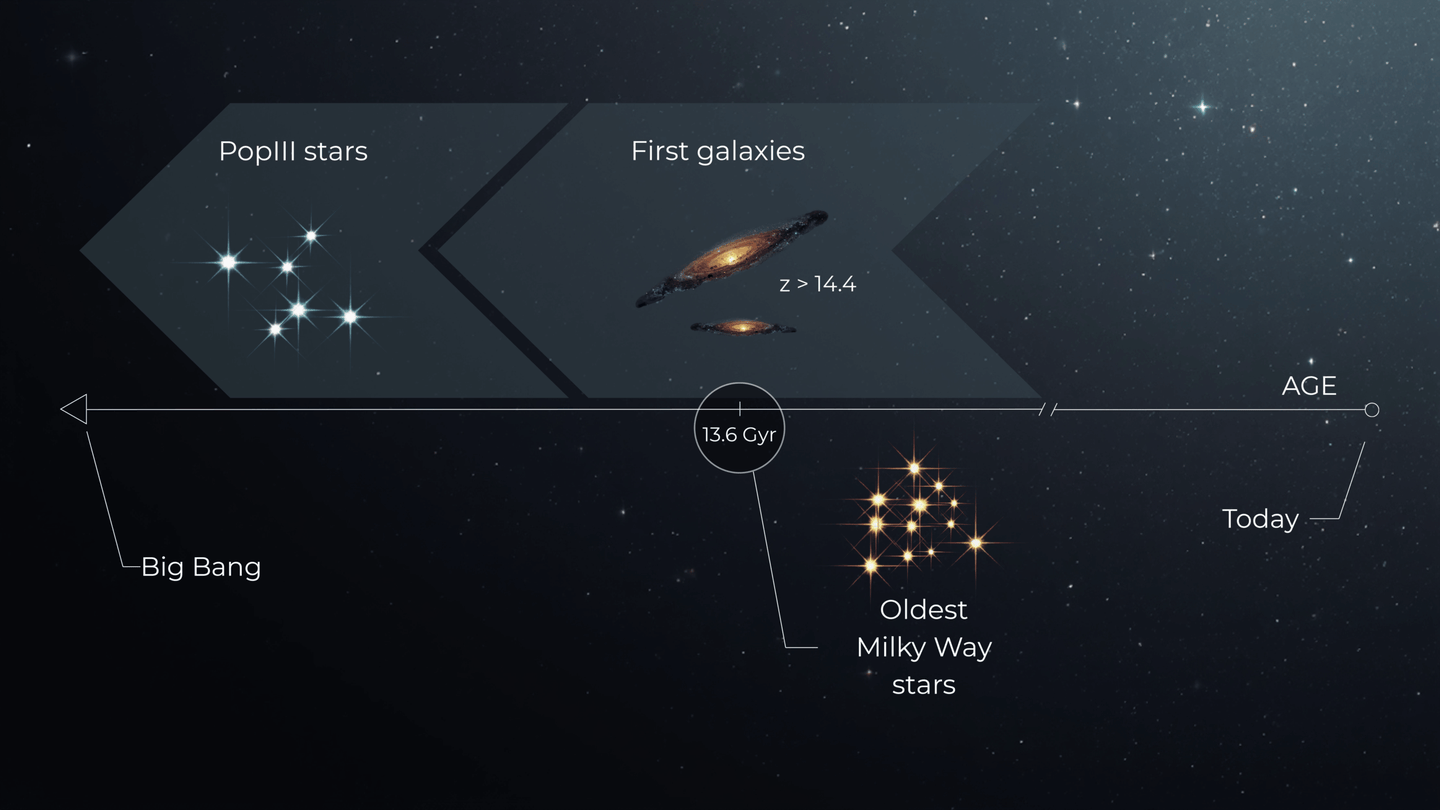

The work may also crack the case of the James Webb Space Telescope’s “little red dots,” faint reddish points from the early universe. A leading idea is that they are young black holes feeding too fast. The new models show how fierce outflows can block X-rays while letting longer-wavelength light through. That would make a black hole look red without needing a burst of newborn stars.

“This agreement between the simulation and observation is crucial,” Zhang said. “It allows better interpretations of the limited data we have.”

A benchmark, and what comes next

For now, the team focused on stellar-mass black holes, which change on human timescales of minutes or hours. Larger monsters evolve more slowly, but the physics is shared. The researchers plan to scale up to supermassive black holes and to compute color predictions that match telescope filters.

“Now the task is to understand all the science that is coming out of it,” said James Stone, an Institute for Advanced Study professor and co-author.

The message is already clear: black holes do not obey a simple brightness cap. When they overeat, the universe hides the excess in motion and direction, not in light.

Research findings are available online in The Astrophysical Journal.

Related Stories

- Red giant starquakes reshape what scientists think about quiet black holes

- If a tiny black hole passed through your body would it hurt you?

- Astronomers solve cosmic mystery surrounding two massive black holes that shouldn't exist

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News' newsletter.

Joseph Shavit

Writer, Editor-At-Large and Publisher

Joseph Shavit, based in Los Angeles, is a seasoned science journalist, editor and co-founder of The Brighter Side of News, where he transforms complex discoveries into clear, engaging stories for general readers. With vast experience at major media groups like Times Mirror and Tribune, he writes with both authority and curiosity. His writing focuses on space science, planetary science, quantum mechanics, geology. Known for linking breakthroughs to real-world markets, he highlights how research transitions into products and industries that shape daily life.